News

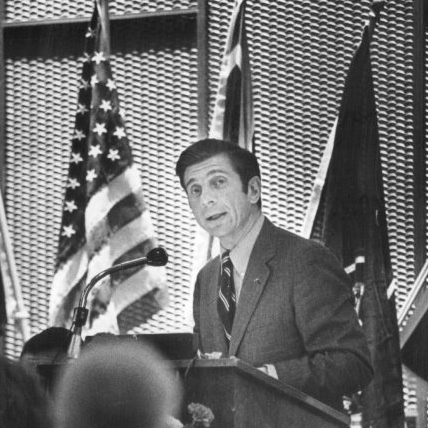

Jewish reporter brought 1969 moon landing into America’s living rooms

(JTA) In the 1960s, astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and John Glenn were household names, idolised as g-d-like figures by a public enraptured by NASA’s (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s) forays into space.

JOSEFIN DOLSTEN

There was also Jules Bergman, who almost attained the same fame in spite of never actually going into space.

The charismatic television reporter covered all of NASA’s 54 manned space flights during his lifetime. One of those was Apollo 11, which 50 years ago, on 20 July 1969, became the first manned spacecraft to land on the moon.

A long-time science editor for ABC News, Bergman was the first network correspondent assigned to cover space full time. That made him “almost as much of a celebrity as the astronauts he covered”, the New York Times wrote in his obituary in 1987.

Bergman, who grew up in New York City, took the subject so seriously that he spent almost as much time as the first astronauts at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. He said he wanted to give viewers “not an ivory-tower discussion of science, but an on-the-spot report of discoveries which are changing the lives of human beings daily”.

CBS’s avuncular anchor, Walter Cronkite, might have been the best-known “face” of the space programme, but the unsmiling, dark-haired Bergman was almost certainly the best prepared.

He took part in various simulations to show viewers the challenges and conditions of space travel, including being subjected to five Gs – five times the force of gravity. He undertook the exercise routine NASA’s astronauts did to prepare themselves for space travel, and spent the entirety of a 12-hour broadcast in a harness identical to one worn by astronauts to measure their vital signs.

“I know that he was incredibly passionate about NASA, and all of space exploration. That comes across even when you watch him,” his nephew, Mark Bergman, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in a phone interview on Wednesday.

The reporter’s legacy lives on even after his death in 1987 at the age of 57. Ten years earlier, Bergman was diagnosed with a non-malignant brain tumour and had surgeries to remove a number of growths. He was also suffering from seizures. The National Association of Physician Broadcasters gives out a Jules Bergman award for excellence in reporting. Footage of Bergman is seen in the Hollywood dramas Apollo 13 and Hidden Figures, as well as countless documentaries.

Though he didn’t speak publicly about his Jewish identity, he was perhaps the only Jew whose public image was so tightly bound with the early space programme. Judith Resnick became the first Jewish-American to go into space in 1984. Two years later, she was aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger, which broke apart shortly after take-off, killing her and the rest of the crew.

Bergman was widely admired for his work, but also had a bit of a reputation among colleagues.

“[H]e was the most disliked person, I guess, in the programme, but he did his homework, and he was real good,” Jack King, who served as NASA’s public-affairs officer, said in part one of the three-part PBS documentary Chasing the Moon, which is airing this month.

Fellow journalist George Alexander also didn’t mince his words.

“There were several prima donnas in broadcasting, Jules Bergman being the pre-eminent example,” Alexander said in the documentary. “Jules wanted you to know that he could have been an astronaut.”

Bergman’s nephew was aware of his reputation, though he said his uncle was “always really nice” to him.

“[H]e was a smart guy doing something that nobody else was doing, so there certainly could have been some jealousy from his competition, and others in his industry,” he said.

He recalled his uncle giving him and other family members a peek into a world few had access to, inviting them into the press area at the Kennedy Space Center and to ABC’s studio in New York.

“Anytime he was on covering a story, it was a big deal,” his nephew said. “A moment to pause at the dinner table. We all had to shut up and listen.”

Bergman was so enthusiastic about flight that he earned a pilot’s license, and wrote about it in the book Anyone Can Fly. He won an Emmy award for his documentary, Closeup on Fire, as well as many journalism awards.

In his work as a reporter, he covered the highlights of the space programme as well as its tragedies. In January 1967, he reported the grim news that three astronauts had died on the launchpad as fire swept through their Apollo 1 spacecraft.

“They died at T minus, 10 minutes into a simulated launch countdown,” he said, “helplessly trapped inside their spacecraft.”

But he also witnessed the triumphs. When Armstrong and Aldrin became the first humans to land on the moon, Bergman described the moment for many of the 650 million people worldwide who were watching on television.

“What’s happening now up there is that at this point, Aldrin and Armstrong are scheduled to, and we have every reason to think they are, eating dinner, like millions of other Americans,” said Bergman, allowing himself a rare chuckle. “Who can imagine any more unusual place for two Americans to have dinner than on the moon?”