News

Jewish tourism businesses on the ropes

CNAAN LIPHSHIZ

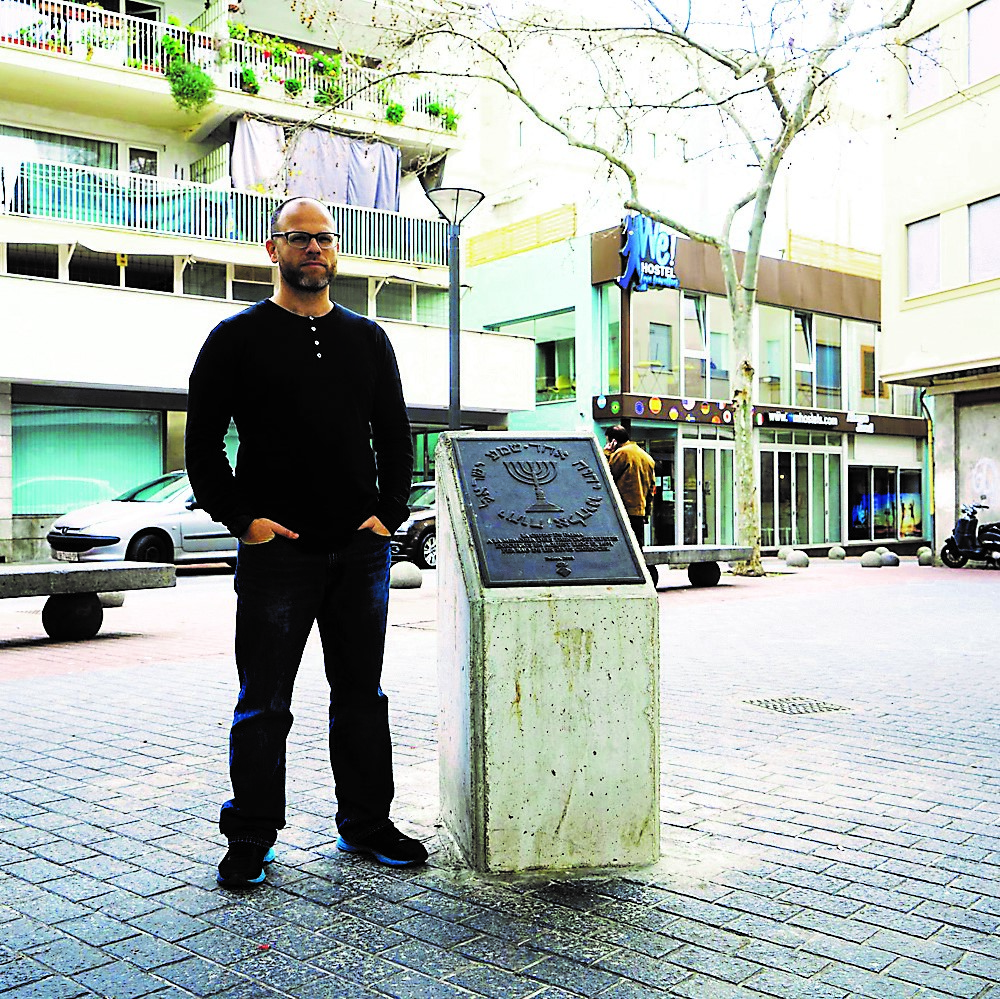

A New Jersey native who settled on the Spanish vacation island in 2014, Rotstein is the founder of Jewish Majorca, the only tourism agency there that specialises in the island’s rich, tragic, and mysterious Jewish history.

With more than 10 million foreign tourists arriving in Mallorca each year, Rotstein’s business, which he set up about a year and a half ago, has succeeded thanks to its unique proposition along with his infectious energy, organisational skills, and slick marketing.

Rotstein recently struck a deal to arrange a programme for 400 travellers who had booked a vacation at a hotel that was going to be made kosher for them. It was the largest booking of its kind in the island’s history, and promised to be a major boon for Rotstein.

“This summer we were preparing finally to see some big earnings,” he said. But then, “everything came to a complete halt”.

That’s because Spain went into a total lockdown to stop the spread of coronavirus, which has killed more than 28 000 people there. This month, instead of welcoming tourists, Rotstein began delivering falafel wraps and hummus to help provide for his one-year-old son and cover expenses connected to his recent purchase of a home in central Palma, the island’s capital.

Rotstein is among the countless operators of tourism businesses worldwide who have been paralysed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a sudden and total end of leisure travel, with no resumption in sight. The future of Jewish tourism businesses, which already cater to a limited clientele and operate on thin margins, may be especially precarious.

A founder of the Limmud Mallorca Jewish learning festival who has had a key role in raising awareness of Mallorca’s unique Jewish history, Rotstein is now developing a model that would allow him to continue giving video tours, mainly to generate interest for when the flow of tourists resumes. But he knows that without deep roots in the tourism industry, he faces an uphill climb. He’s thinking about leaving the island and his dream career.

“It caught us at a vulnerable point where things were just getting ready to take off, but before we got a chance to establish ourselves with many people,” he said. “It’s very frustrating.”

In Warsaw, 61-year-old Maimon Ben Ezra estimates that his kosher restaurant Bekef, one of only a handful in that category in the Polish capital, will go bust in about two weeks.

Ben Ezra, an Israel-born chef who settled in Poland 13 years ago, recently invested $100 000 (R1.7m) to expand and move his successful business as a response to the massive rise in recent years of the Central European country as a holiday destination for Israelis and other Jews.

“I signed the contract two weeks before the crisis hit,” Ben Ezra, who has an eight-year-old daughter with his Polish-Jewish wife, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The upgrade transformed his local neighbourhood eatery of about 20 seats into a 90-seat diner with two floors and the facilities and staff to handle large groups.

Ben Ezra moved the restaurant to the former Jewish Ghetto, a must-see for Jewish tourists, and rented a venue next door to the Warsaw Jewish Ghetto museum, which is scheduled to open next year.

“This was supposed to be the first time that we could actually service March of the Living groups,” Ben Ezra said, referencing the tens of thousands of Jewish teens and chaperones from across the world who come to Poland each spring for a Holocaust commemoration event. “It was supposed to help us pay for the investment.”

But this year’s march was postponed indefinitely because of COVID-19. Ben Ezra couldn’t get out of his contract for the new venue and had already invested in setting up there. To make ends meet, he now provides catering services. But Warsaw has several businesses like that, and only a few thousand Jews.

“I’m stuck. It feels like I’m drowning in quicksand,” Ben Ezra said.

Unlike Warsaw and Mallorca, Amsterdam already is an established Jewish tourism magnet.

Combining unique Jewish heritage sites for older visitors and families with other amenities that tend to appeal more to younger arrivals, the Dutch capital has dominated the charts of holiday destinations for Israelis for decades.

But here, too, the COVID-19 crisis is casting doubt on the survival of some firms that cater to Jewish tourists.

For We Are Amsterdam, a Jewish-owned Amsterdam boat rental and tour operator agency, the problem won’t be getting brand recognition. Rather, distancing requirements to prevent the spread of the disease would impede its ability to serve a predominantly Israeli clientele even if travellers return.

Guy Kuttner, a former sailor in the Israeli Navy, launched the business two years ago with his Dutch friend Timo Haaker. It was going well, with families and groups of friends booking as much as the We Are Amsterdam team could handle. The business, which showcased insider knowledge of the nightlife scene on its tours as well as Jewish history, recently began branching out to visitors from China.

Kuttner and Haaker moved the firm to a new building on Herengracht, one of Amsterdam’s priciest streets, and had grown to 25 employees when the COVID-19 crisis abruptly ended travel. Now as the Dutch capital begins allowing businesses to operate again, social distancing rules mean that even if tourists begin visiting the city, We Are Amsterdam can’t bring enough customers onto its 32-foot (9.7 metre) boats to turn a profit.

“Our whole business model is based on offering a much more intimate personal feeling than what you get on one of those large canal boats with a guided tour through earphones in 17 languages,” Kuttner said.

Like Rotstein in Mallorca and Ben Ezra in Warsaw, the Dutch boating partners have explored ways to keep their business afloat. Using 3D cameras, they created a virtual, interactive canal ride where viewers can scroll around for a 360-degree view of Amsterdam seen from its waterways. But the virtual canal cruise is free, meant as a marketing tool and a way “to maintain a presence”, Kuttner said. “It doesn’t help cover overheads.”

We Are Amsterdam also offers land excursions, including an Amsterdam windmill tour. But social distancing has halved the capacity of 10-seat minivans, making such excursions less than cost effective, Kuttner said.

The coronavirus crisis is hurting noncommercial Jewish tourist attractions, too. In Prague, the loss of millions of dollars in revenue from sales of tickets to the city’s Jewish cultural quarter means shortages in available funds for welfare work, some community leaders said.

In Hungary, a debate erupted over the decision by the Mazsihisz federation of Jewish communities to renew its $290 000 (R5.1m) contract with a private firm that takes care of the tourism aspects of Dohany Synagogue, a popular attraction whose future as a communal cash cow is now in doubt.

Yet European Jewish communities, many of them operating on funds given as compensation for Jewish property lost or seized in the Holocaust, have a better chance of weathering the storm than individuals who make their living from Jewish tourism.

The crisis abruptly ended the income source of Anne-Maria van Hilst, a 32-year-old tour guide from Amsterdam who specialises in its Jewish history.

“I didn’t get into this work to make money, I do it because it’s what I’m passionate about,” said Van Hilst, who converted to Judaism more than a decade ago. “But suddenly it stopped, and it’s not clear when and how it will be possible again, and I, and many other people in this sector, are suddenly questioning our choices and rethinking everything.”