News

Jewish trends tell a tale of three cities

Did you know that Joburg Jews have more financial challenges than Capetonian Jews, but they are also much more likely to employ domestic staff than their coastal counterparts?

TALI FEINBERG

While the South African Jewish community is a cohesive one in many ways, these are some of the fascinating differences between its population centres revealed by the recently released Jewish Community Survey of South Africa (JCSSA).

At the same time, Jews may be spread out across the country, but they also live close together. The JCSSA shows that more than half of the respondents live in just four postcodes of South Africa, and three-quarters of the entire Jewish population lives in just sixteen postcode areas.

“In short, the key differences between Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban relate to age and religion,” says Associate Professor Adam Mendelsohn, the director of the Isaac and Jessie Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research at the University of Cape Town.

However, he doesn’t believe age and religious differences make these communities “separate”.

“There’s still a spectrum of religious identity in each city, a lot of movement and connection between all three cities, and more in common than not. In reality, there have always been differences between [and within] these communities,” Mendelsohn says.

Does this mean that local communities could come into conflict with one another? “This data does suggest that there is some divergence – and potential areas of tension – between them, particularly relating to matters of religion,” says Mendelsohn. “There are still many things that most but not all South African Jews agree on, but we can expect further flare-ups around matters where cities are pulling in opposite directions.”

Regarding the tendency of the community in Johannesburg to be more religious than in the other cities, Mendelsohn says, “A lot has been written and is being written about why Johannesburg has become more religious. A variety of factors have been at work for a long time. In Johannesburg, this pattern has often been traced to the influence of several charismatic religious leaders and movements that took root in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Others look back further, and suggest that each of these communities have always had a different character, in part because of the scale and nature of the Lithuanian Jewish immigrant population in each, and the dominant ethos of the city itself,” he says.

In addition, “The relative success of the progressive movement in each centre has its own history, again in part reflecting the key role played by particular individuals in each setting. Irwin Manoim’s new book on the history of the progressive movement in South Africa explains much of this divergence. To a certain extent, the religious trajectory in each city has become self-reinforcing, for example, young people in search of a larger and more vibrant Orthodox community have moved to Johannesburg.”

From the JCSSA report, it’s clear that Joburg has the youngest population. This is probably related to it being a more Orthodox community, with 30% of its members aged 18 to 40 compared with 16% in Cape Town, and 7% in Durban, which has the oldest population.

Of the Jews living in Johannesburg, 34% are aged 60 and above. In Cape Town, the equivalent proportion is 46%, and in Durban, 58%. In Durban, 20% are retired, compared with 18% in Cape Town, and 12% in Johannesburg.

The study offers fascinating data on religious identity in the different population centres. In Johannesburg, almost half of the respondents (48%) described themselves as either Orthodox or strictly Orthodox, compared with 22% in Cape Town, and 28% in Durban. In Cape Town, 40% described themselves as progressive or secular, compared with 18% in Johannesburg.

Intermarriage statistics also offer insight into these differences. A total of 12% of all Jews in South Africa are intermarried: 6% of Joburgers, 18% of Capetonians, and 29% of Durbanites.

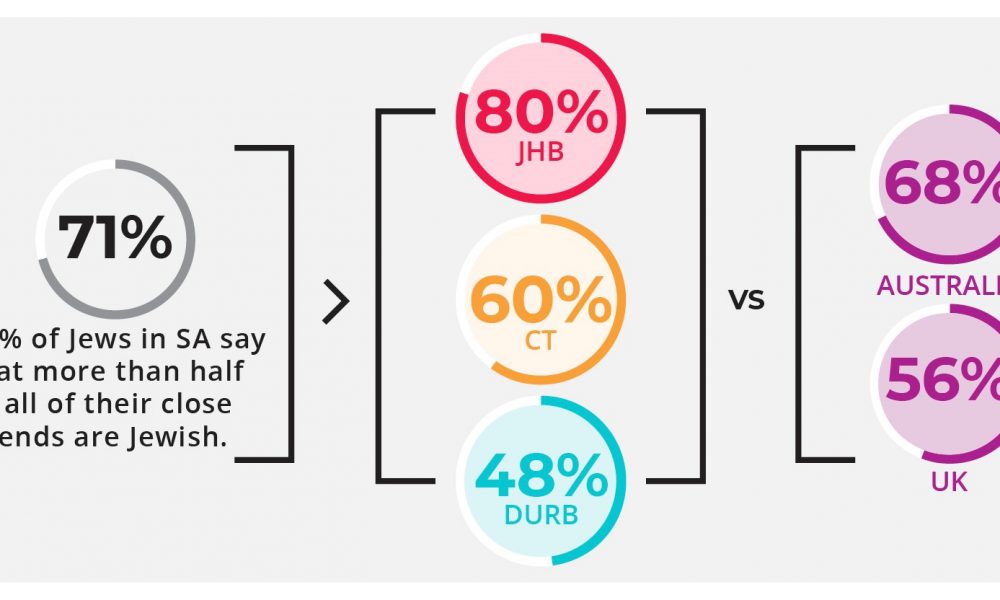

The South African Jewish community appears to be close-knit across the board. This is particularly prevalent in Johannesburg, with 80% of Jews saying that more than half or all of their friends are Jewish. In Cape Town, the equivalent proportion is 60%, in Durban, it’s 48%.

There are other differences. Joburgers, for example, may be facing a greater financial struggle. A total of 28% in Johannesburg describe their socio-economic well-being as “just getting along” or “poor”, compared to 23% in Cape Town, and 18% in the remaining areas. At the same time, 51% of respondents in Johannesburg employ at least one full-time member of staff at home compared with 32% in Cape Town.

The survey suggests that there has been movement from Johannesburg to Cape Town over the past five years: 3% of Joburgers lived in a different part of South Africa five years before the survey, compared to 6% of Capetonians. “It’s likely that a net Jewish population flow away from Johannesburg towards Cape Town took place over this period,” surmises the report.

A total of 37% of respondents said that they were likely to move from their current location in the next five years (whether to a different suburb, city, or abroad), and the top reason given for wanting to live in a different part of South Africa is to seek a better lifestyle.

Asked if he thinks this trend will continue, Mendelsohn says, “We can assume that migration to Cape Town and Durban will continue, particularly among retirees. But this flow isn’t unidirectional. There is clear evidence of people moving to Johannesburg for work, in search of a particular religious experience, or because their friends have moved there.”