News

Jews and alcohol – and the close bond between them

JORDAN MOSHE

Because there is another figure whose role in peddling alcohol was just as controversial and perhaps even more influential: the Jewish bootlegger.

Although the exact number of people involved in bootlegging during Prohibition in the United States between 1920 and 1933 is not known, evidence of almost 60% of them being Jewish exists. In fact, commonly believed bootlegger stereotypes are inaccurate, with research suggesting that only about 30% were Italian and 10% were Irish.

“At first, alcohol offered a way for American Jews to present themselves as the best sorts of Americans, as the ones who consume alcohol regularly but are not drunkards, who participate in the economy in ways that benefit communities and society at large,” writes Marni Davis, author of Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition.

The close connection between Jews and alcohol can actually be traced back further than the US of the early 20th century. Jews had been fierce opponents of temperance and prohibition efforts since the 1870s, for both economic and cultural reasons. Long before the ban on alcohol, Jews were deeply involved in the alcohol business.

Wine is an important component of Jewish religious practice, traditionally and historically. It is blessed and drunk at tables on Friday night and Saturday morning in honour of Shabbat. Jews are instructed by halacha to create their own wine, which can’t involve anyone outside of the faith. Jewish cultural practices also separate us from other communities.

This, as Davis explains, gave rise to the economic connection. If Jews were overseeing the entire process of wine-making, they could increase their expertise and capitalise on the manufacture of wine.

Insofar as both wine and beer were concerned, Jews produced drinks for their own consumption and that of their gentile neighbours for centuries. The Jews of Persia made a living from brewing beer. Jewish communities who were part of the Islamic empire of the Middle Ages produced wine for Muslims who sought a clandestine supplier. They served as brokers and middlemen, trafficking alcohol across a vast network, thereby situating themselves centrally in an important commercial market.

This was particularly important for American Jews in later years. Alcohol commerce was a driving force of social mobility for Jews, enabling them to reach new heights and better their prospects. The threat posed by Prohibition imperilled not only this means of life improvement, but represented a xenophobic movement in the US. This was a concerted effort to keep immigrants and religions like Judaism and Catholicism away from the mainstream.

The American Jewish Committee, B’nai B’rith, and other Jewish organisations opposed Prohibition because of its larger implications. They saw it as pushing a more sinister association between those considered “the other” and alcohol, and stressed the danger that both represented a moral American public.

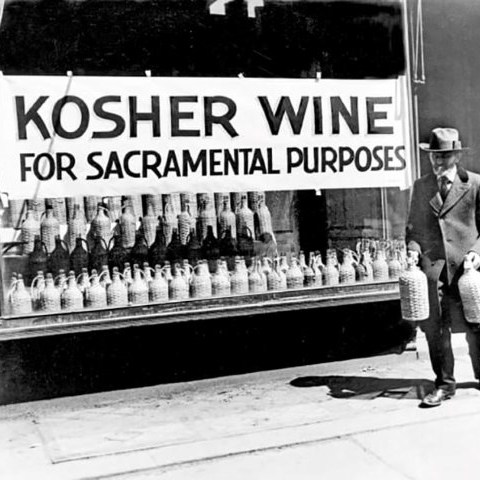

When Prohibition was enacted, a heavily Jewish industry effectively became an outlawed one. Under the Volstead Act, wine consumption was still permitted for sacramental purposes, and rabbis and priests alone could legally possess and distribute it.

Every Jewish adult in the country was allocated 10 gallons of wine a year. This restriction had the amusing effect of seeing a single Los Angeles congregation rise from 180 families to 1 000 families in a single year. By 1924, 2.9 million gallons were being given out, causing many to think, mistakenly, that the Jewish population was growing.

Because the rabbinate in the US was very loosely organised, it wasn’t long before Jewish communities witnessed an increase in the presence of “rabbis” with unusually large congregations.

When a federal grand jury investigated 600 rabbis in New York City in 1926, the amount of wine drawn from the strictly sacramental wine storage locations suddenly dropped from one million gallons in 1925 to 6 000 gallons in 1926. Their suspicions were clearly confirmed.

Alongside bootlegging rabbis, Jewish involvement in moving other alcoholic beverages was no less impressive. The Canadian businessman Samuel Bronfman, owner of Seagram Gin, had Jewish bootleggers floating so much illegal liquor into the US over Lake Erie that it became known as the “Jewish Lake”.

In fact, says author Daniel Okrent, almost half the bootleggers who pumped the US with alcohol during Prohibition were Eastern European Jews, including real-life gangsters such as Longie Zwillman, Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel. The Jewish cohort of notorious mobsters was sizeable. Lansky and Siegel ran the Bugs and Meyer Mob, which later became a part of Murder Incorporated, a key part of the bootlegging enterprise and the brutal enforcement arm of the Italian Mafia.

Jews were also represented on the side of the law, with federal agents such as Izzy Einstein accosting elderly bearded Jewish men pushing prams through the Lower East Side and discovering that they contained “the cutest tot of whisky he ever saw”.

Whether for religious practice or pleasure, Jewish bootleggers ensured that the alcohol kept flowing in the US at its driest time in history. Although unlikely allies, rabbis and gangsters worked side by side, united in a mission that would see Haftorah clubs and Pesach Seders alike kept well supplied with the necessary tipple.