Tributes

Laughter inducing and life saving – farewell Uncle Harold

My uncle Harold (Professor Harry Seftel, who we in the family called Harold) was a force of nature. His genius never failed to blow us away. We never went to doctors because we had Harold. No matter where any of us were in the world, one call to Harold about an ailment, and he would prescribe the cure. We grew up knowing that whatever we did was measured against what Harold said. What we ate, what medications to take, and how best to heal. We did nothing without Harold.

Our family get-togethers were the best entertainment in the world. Harold held forth, and kept us in fits of laughter. He had sayings and slogans that had every South African who listened to him on Radio 702 roar with laughter.

His deep voice boomed across lecture halls; radio stations transmitted his words into the homes of millions of his devoted listeners. He was in his element while he did what he loved. To teach and educate generations, delivered in his unique style with alliteration catch phrases and humour. Harold got away with saying things that no-one else would have. He swore, he used words that weren’t found in medical journals, and no-one objected. It endeared him even more. Medically speaking, he was in a league of his own.

“The fatal s’s: slothing, sexing, snogging, stuffing, and stressing,” emphasising the s’s and r’s with his signature guttural growl.

“Fish, fowl, and fibre,” was another favourite.

“So, in order to pass a good, normal stool you should eat grass, not smoke it,” was one of his classics.

I asked my cousin, Lewis, if he had any stories he remembered that I could write about in this article. We laughed as we shared memories about growing up with this remarkable man. He reminded me of Harold’s study practice growing up in Mayfair when the house was too tumeldik to study. He went onto the roof where he could study in silence. If the neighbours needed him, they got his attention by throwing stones onto the roof. He was so deeply engrossed in his studies, it was the only way they could communicate with him.

My bobba was called to the school one day by Harold’s teacher.

“Mrs Seftel, I’m sorry to tell you this, but your son is backwards.”

“Oy, tank you, tank you,” my bobba replied, her English not very good at that time.

The teacher looked at her, frowning with impatience and repeated herself.

My Bobba smiled broadly. She knew Harold was a genius, and presumed the teacher called her in to tell her she knew it too.

Harold studied Latin at school, which was unusual because it wasn’t a requirement. He loved it so much, that he then taught himself Greek. When he started studying medicine, it was like coming home. It was his natural environment – medical terms and anatomy were in Latin.

As much as Harold loved Latin, he loved words, and he loved the way words sounded. He believed that when he described a disease in Latin, he educated people with both a scientific lesson and a grammar lesson. His unique teaching skills taught people about the origin of language as well as about medicine.

A relative complained once that he had an itchy tochus. Harold said, “Ahhh you have an old friend of mine down there. Taenia Saginata,” he pronounced in his loud deep voice, savouring each letter, his awe for Latin never diminishing. “You have tapeworm. We’ll kill him, don’t worry.”

“How do you know I have tapeworm?” my relative asked.

“I know you’re a good Jewish boy, so I know you don’t eat pork. The one that comes in pork is Taenia Solium. You obviously ate beef in the canteen at the university, and that’s where you got my old friend.”

Harold’s combination of theatre and language, and how he connected it with medicine made him extraordinary – the theatrical and the scientific.

Lewis related a lecture Harold gave on the importance of breastfeeding.

“Women must use their breasts for babies and not for commerce and titillation,” Harold announced, punctuating the r’s.

“You are using your breasts for business; your tits must not be used for titillation. They must be used for babies,” he would tell an audience as they fell into the aisles laughing. “The phenomenon that we have today is a babyless lady. A babyless lady is a terrible thing. You don’t want to be a babyless lady. That’s what makes you healthy.”

“How do you remember this,” I asked as I couldn’t stop laughing.

“Because of the way he spoke. He was so theatrical and it all had to do with language.”

Harold was a national treasure and to us family, he was our hero. He was our everything, and we adored him.

Nothing gave me more pleasure than cooking for Harold. His eyes lit up when I baked him boolkas, herring and kichel had him sigh with deep pleasure, and chicken soup with bobba’s kneidlach set him off on an endless round of compliments.

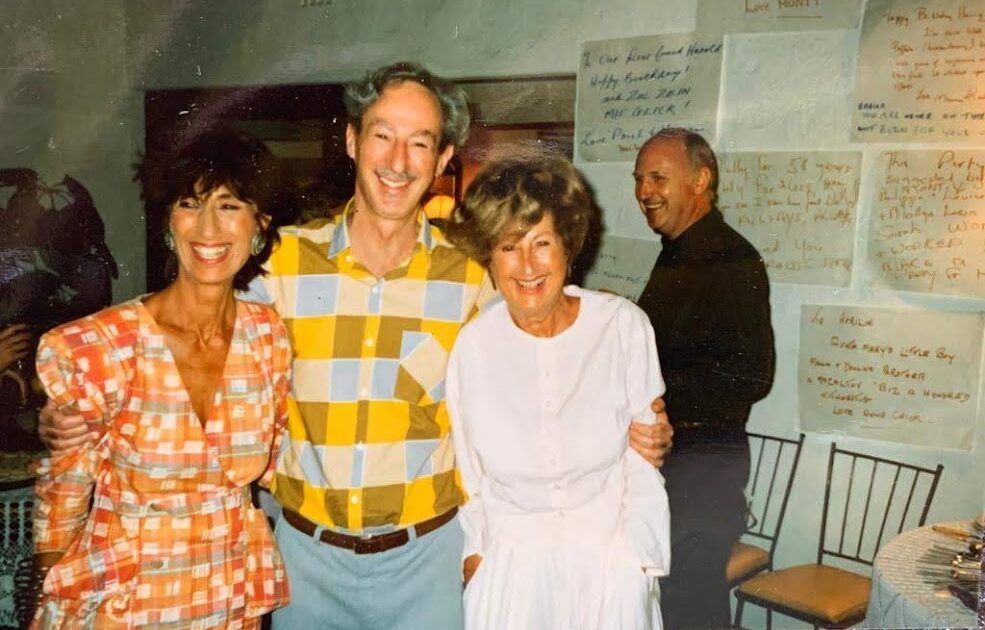

I had another reason for loving Harold as much as I did. When I gave birth to my second son, I was bleeding to death. My gynaecologist panicked and ran out of the theatre to tell my mother to call Harold. I went in and out of consciousness, and one of the times I woke up I saw Harold standing beside me. I thought it odd that he was in the theatre wearing a brown checked shirt and a pair of shorts. When I woke up later in intensive care, I was told that Harold had saved my life. He had instructed my gynaecologist what to do.

I will share another story about how extraordinary a man he was. I did something quite awful, and I went to Harold to apologise. He took me in his arms and said, “Philippapala – only he and my bobba called me that – we have the same blood.” I burst out crying, and hugged him hard.

Harold, you live on in all of us every day. We quote you regularly, and talk about you constantly. You are still our everything.

Philippa Sklaar is the author of three books, Hot Cuisine, a recipe book written on men and food, and co-wrote When Loving Him Hurts and The Affair. She is working on her second recipe book.