Lifestyle

Mangoes and the Queen Mum: new book documents Jews of Kampala

Janice Masur is keeping alive the memory of one of many Jewish communities that disappeared in the past century – the Jews of Uganda.

The history of Eastern European Jewry in Kampala had all but died out when Masur recently brought out a book believed to be the only one devoted to the Jewish community in the capital city of Uganda.

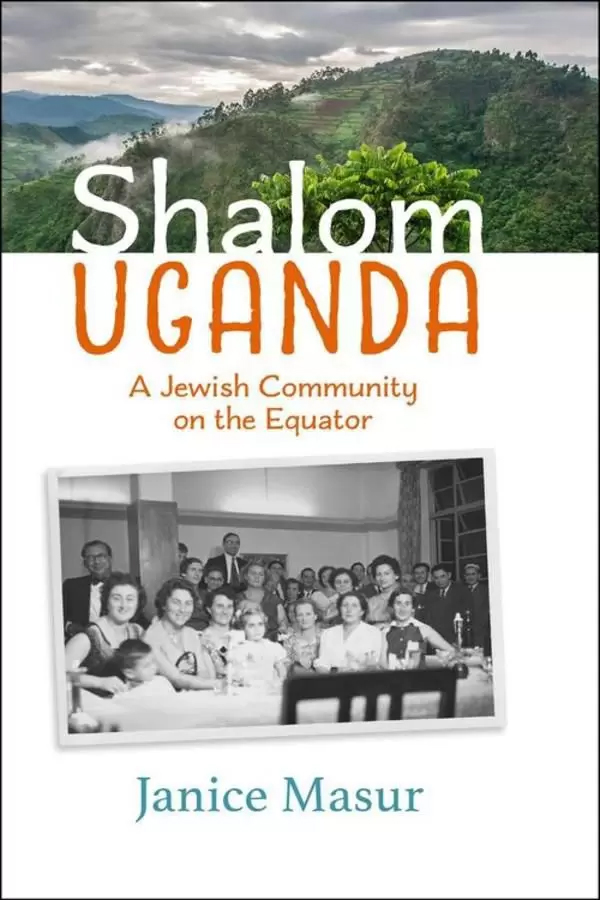

Titled Shalom Uganda: A Jewish Community on the Equator, the well-researched book begins with a historical overview of Jews in Africa, and goes on to tell Masur’s story of living in a little-known Ashkenazi Jewish community in Kampala from 1949 to 1961.

Although this tiny and remote community had no rabbi or synagogue, its 23 families formed a cohesive group that celebrated all Jewish festivals together and upheld their Jewish identity. Sadly, while Kampala Jewry made every effort to survive, the community eventually withered under the hot African sun, leaving few traces of its existence.

However, Masur’s desire to bear witness to the place where she spent her childhood has resulted in its history being preserved in this compelling memoir, supported by interviews, photographs, and in-depth research.

The idea for the book originated in a modern East African history class she attended at Simon Fraser University in Canada. She began writing in 2005, travelling to interview octogenarians and nonagenarians who had arrived in Kampala earlier in their lives.

Masur herself was born in Eritrea, where her parents chose to move from Palestine in 1942, presumably for better job and financial opportunities. They settled in Uganda in 1949 after Masur’s father, Helmut, was hired to manage the isolated Kampala Tile and Brickwork Company.

“I am a second-generation Jewish woman and have only one cousin who joined us in Kampala with his family,” Masur told the SA Jewish Report from her home in Vancouver, Canada. “We visited South Africa in 1961 when travelling by car from Uganda to Durban – and stayed in a Jewish hotel – to board a cargo ship which deposited us in New Zealand [where she attended university].”

Today, she is strongly rooted in her Jewish community in Vancouver, where she lives with her husband.

“I visited South Africa again in 2001, meeting a childhood friend in Cape Town,” Masur said. “I visited Namibia in 2010 – not really South Africa.”

In one of the anecdotes as a nine-year-old in Kampala, Masur writes in her book that “a rabbi was imported from South Africa for Yom Kippur” in 1953. He stayed with her family, and held the service in their house. Her parents told her to eat breakfast in the bathroom so that the rabbi would be unaware of her not fasting.

“Many years later, I learned that children under the age of 12 were permitted to eat on the fast day of Yom Kippur, so it seems that Jewish law wasn’t fully understood. Still, my parents did their best with whatever they remembered,” she writes.

Masur shares another experience in her book, the significance of which she discovered only later in life. While living in a single-level house that had an avocado tree and a badminton court, she often saw her family’s “houseboy”, Odera, dancing and singing around the house.

“My mother spent a lot of time screaming at the houseboy in frustration at his supposed inability to follow instructions, which I later learned was a passive tactic of rebellion against British rule,” she writes.

From 1957 to 1960, she attended the government (semi-private) Highlands School in Eldoret, Kenya, and noticed that post-war antisemitism was endemic. “Unkind girls in Eldoret would sometimes bully me by telling me that I was a misfit because my nationality was Jewish, not British, although I was naturalised British and my religion was Jewish!” she writes.

On several occasions, Masur stood with her mother in the driveway outside the gates of Government House in Entebbe with a crowd of other people to watch the arrival or departure of Princess Margaret, Queen Elizabeth II, and the Queen Mother.

In preparation for the visit of the latter in 1959, all the shops on the main street were scrubbed and painted, the road islands were dolled up, and flags and bunting feverishly bought. To meet the dress requirements, Masur’s mother and aunty had to borrow gloves and hats from friends. Soon, the duo laughed to see their picture shown on the front page of the Uganda Argus newspaper with the Queen Mum.

Masur hasn’t returned to Uganda since leaving Kampala for New Zealand as she thinks that “perhaps memories are best left to glitter in the distance”.

That said, her formative years in the country have left a lasting imprint. “To this day, I love mangoes, and growing up in Kampala has made me feel comfortable in the company of all ethnic groups,” Masur recently told the Canadian website Jewish Independent.

Today, Uganda has about 2 000 observant Jews known as the Abayudaya – the “people of Judah”. Having converted to Judaism in passive rebellion against British rule in 1921, the Abayudaya is a now-thriving, self-sufficient black Jewish community in Mbale, boasting synagogues, Jewish schools, a mikvah, and a cemetery.

However, there isn’t even a cemetery to mark the existence of Masur’s family and 22 others who managed to create an Eastern European Jewish community in Kampala. Masur hopes that her book will document and honour what she describes as “an imploded star vanished in the diasporic galaxy”.

Hessel Meilech

September 17, 2021 at 12:18 pm

Rabbi Silberhaft the travelling Rabbi would be very interested in this article.