Featured Item

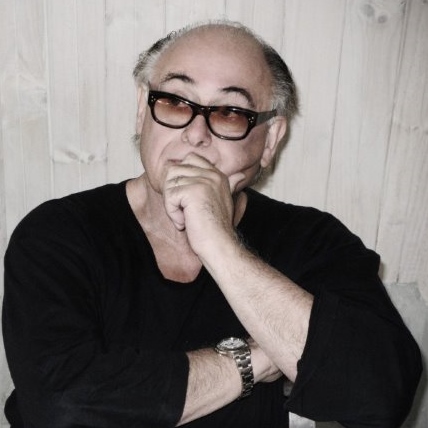

Michael Meyersfeld – the liberated eye

When one thinks of photography of a personal nature, what springs to mind is the ability to share images online with a relatively unconfined group of “friends”. It leads one to wonder: How personal is personal really?

MATTHEW KROUSE

The hazards of socialising in the 21st century have led to an ongoing crisis of privacy, mainly in photography. We’ve gone beyond the personal as merely political. In the war of images, one can be condemned for what one chooses to share.

In this way, photography as a pastime, journalistic device or art form has become an event. As the renowned (read radical) Israeli academic Ariella Azoulay has noted: “One needs to stop looking at the photograph and to start watching it.”

It’s a piece of advice that could assist one greatly in approaching the new works of Michael Meyersfeld, even though his recent photography does not attempt to be politically or socially relevant. Which is not to say that he hasn’t in the past made statements through his work.

His first book, titled Gaze (2003), was quite an event – at least in my life. I remember paging through his portraits of unclothed gays and lesbians with a mixed sense of wonderment and wondering why the “community” needed to be portrayed in its nakedness. At the time, I was exploring Jewish identity and I remember thinking how contentious it would be to present a book of only naked Jews.

But that influential and highly visible gays and lesbians allowed Meyersfeld to “gaze” upon them with his camera did mean something – primarily because he is a starkly individualistic image maker who knows where to draw the fine line between voyeurism and timeless artistic construction.

It’s important to say at this point that this is not what his latest series of images is about. But as background it’s interesting to know where Meyersfeld has come from. He is one of the country’s most senior commercial photographers and you’ve probably seen his photography in countless adverts, including for Vodacom and Mercedes. So, his work forms a part of our collective unconsciousness.

His creative projects have included remarkably large nudes in his series, 12 Naked Men (2005), and the fabulous dramatic tableaux of Guests at the Troyeville Hotel (2010), among many others. Some of it is sexy, some tends towards dramatised documentary (if there is such a thing), but none of it is depressing. In his artist’s statement about his life’s work Meyersfeld gives us a clue to his overall motivation: “As it is not rooted in fantasy, this allows me to avoid the ugly underbelly of reality.”

In other words, his constructed visual dramas are rooted in experience.

Which leads us to his current exhibition, entirely in black and white, aptly named Accessing the Encoded. It’s probably the most sombre series of images he’s done. In contrast to his previous work, he says, “the images on show are not representational; there is no defined narrative, nor have they been staged or planned. They are intuitive and could be read as abstractions, requiring an eye liberated from the dominant quest to find and attach a defining narrative.”

There’s a photograph of the tiled end of a swimming pool (titled “Retreat”) and various types of foliage. One is textured in such darkness that it seems like ancient wallpaper. There’s a large and pale photograph of the most gigantic scaffolding construction in a mysterious scale (titled “Hive”), and ripples around a leaf in a puddle (titled “Echo”).

This is the result of a slow percolation by the photographer; time spent alone ruminating on the state and quality of things beyond human.

In his introduction to the exhibition, critic and curator Johan Myburg said: “We are so used to seeing things and attaching labels and meaning to them that we seldom look deeper and do not see things in their specificity.

“One function of art is to make the familiar strange. And this where we enter the world of semiotics, the world of the signifier and the signified, the world of ‘Accessing the Encoded’, the title of Meyersfeld’s exhibition.”

By making the familiar seem less so, Meyersfeld is using photography as a sort of meditation. It seems he is returning to the essence of creativity as a process of looking outward, in order to look inward.

- The exhibition runs at Gallery 2, 138 Jan Smuts Avenue, Rosebank, until 28 July