Featured Item

Microscopic study, macroscopic findings for Nobel laureate

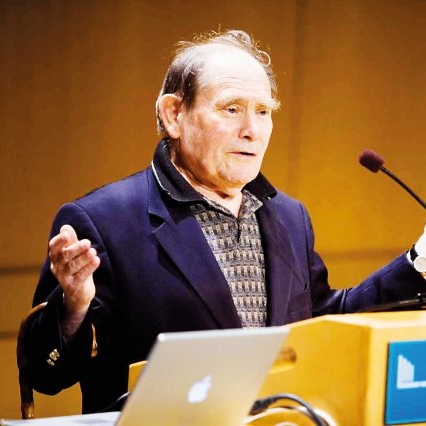

JORDAN MOSHE

Brenner devoted himself to studying the genetics, development, and behaviour of a tiny nematode worm. What he gleaned would enable him to make a great contribution to our understanding of human disease, and would be recognised in 2002 with a share in the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

“Sydney Brenner was a hero in the field of modern biology,” says Howard Horvitz, an American biologist with whom Brenner and John Sulston shared the Nobel Prize. “His contribution to our understanding of genetics – what makes a child more similar to its parents than to a redwood tree or a whale – are unparalleled.”

Born in Germiston to a Lithuanian father and Latvian mother in 1927, Brenner grew up in a home at the back of his father’s cobbler shop. He was said to be insatiably inquisitive, and he progressed so rapidly through school that he obtained a bursary to pursue medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand at 15. Because he would be too young to qualify for medicine at the conclusion of his six-year course, he was allowed to complete a Bachelor of Science degree in anatomy and physiology.

After doing an honours degree and then an MSc, he went on to receive another scholarship which enabled him to complete a Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Oxford as a postgraduate student of Exeter College.

It was while at Oxford that Brenner set himself upon his life’s path. Together with a handful of others, he was one of the first people in April 1953 to see Francis Crick and James Watson’s model of the structure of DNA, a watershed in his scientific life.

“I just knew that this was the beginning of molecular biology,” he wrote later. “This was it… the curtain had been lifted, and everything was now clear as to what to do.”

Brenner would not only go on to work with Crick for 20 years at Cambridge’s molecular biology research unit, but would draw inspiration from him to develop his own research. After working extensively on DNA research and the makeup of amino acids, Brenner leapt from molecules to whole animals, choosing a microscopic worm to establish how genes-controlled development and behaviour.

In 1966, Brenner recruited a team of researchers, among them Sulston and Horvitz, who mapped and sequenced the worm genome. Their work would eventually be recognised as a major contribution to their field, and awarded the Nobel Prize in 2002.

His work made a sizeable contribution across the globe. In the mid-1990s, Brenner crossed the Atlantic to establish the Molecular Sciences Institute in Berkeley, California, and in 2000, he became a distinguished professor at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. He was director of the Medical Research Council’s prestigious Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, and maintained a close connection with Singapore, where he was an honorary citizen, and whose medical-research capacity he enhanced over 35 years. He was also the recipient of numerous awards for his work.

Beyond his scientific prowess, Brenner was admired by his colleagues for his sharp sense of humour and wit. For seven years, he wrote a sardonic monthly opinion column for the science journal, Current Biology, under the alias “Uncle Syd”. He once wrote, “Elderly, white, male, column writer, seven years’ experience, self-employed scientist, explorer, adventurer, inventor, and entrepreneur seeks young, naïve, preferably female editor of newly formed scientific journal with a view to obtaining unrefereed access to as wide an audience as possible.”

Says Horvitz, “His brilliance, wit, and the twinkle of his eye reflecting a sense of always enjoying life, and provided insights and lessons to all who had the privilege of being close to him. I have no idea what my life would be had I not had Sydney in my life for so many years. I miss him, and always will.”

Married to fellow South African May Balkind until her death in 2010, Brenner leaves behind three children, Stefan, Belinda, and Carla.