Lifestyle

Moving mountains – SA architect honoured with blue plaque

Here’s a true story, from when I was growing up. The year was 1969, and we had just moved into a glass and pine layered box pegged to the side of Linksfield Ridge. My father, Gerald Gordon, was the architect, and the house was featured in various newspapers at the time, front page of the Sunday Times property section, and so on.

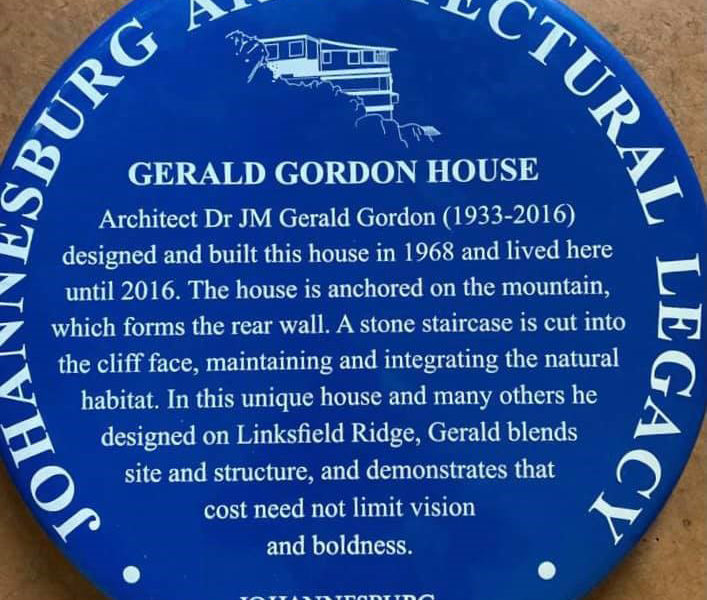

Fast forward 52 years, and this same house now bears a Johannesburg Architectural Legacy blue plaque, reflecting on both the house and its designer. And the story is worth its retelling because opening your eyes and pushing back against the derivative and the ersatz matters. Well, it mattered to Gerald.

It was a different time, and objects of even acceptable imagination hardly existed in the South African shops of the era, so he made his own: light fittings, kitchen finishes, sofa frames, etc. Once he made a set of wine “glasses” by welding caramel cups to upturned bedsprings. Yeah, okay, not every idea worked.

Even as the fount of visual ingenuity was in full flow, for Gerald, design was never merely aesthetics. It was about finding the optimal solution. And what was the optimal solution to this house? There was a cliff-face, there was a patch of flat ground below it, and below that more falling mountainside.

That there was any flatland at all was due to the stone-wall topography of Linksfield Ridge left by Dr Hermann Kallenbach, a landscaper and stonemason of unparalleled ability, to say nothing of energy. Jewish too, by the way. And now also recognised with his own Johannesburg Heritage Society blue plaque.

Now, if you put your house on the flat, bang goes the garden and pool. How’s that going to go down with the family? So, Gerald hung it on the mountain. With the front door, let me airily say, at roof level. You need brass kahun … oh alright let’s call it chutzpah to do this. I know this may seem odd to you – hell it is odd – we had koppie and mountain shrubs in our living room.

Gerald was born in Vryheid. How and why his Lithuanian parents got there is a story lost in time, but the family moved to Johannesburg specifically so his elder sisters could find nice Jewish boys (which they did), and Gerald had a Barmitzvah in the Yeoville Shul.

He was at the time also a Betarnik. I’ll leave it to you to work out whether this was more about ideology or the free summer holidays, but one way or another he progressed from that and Athlone Boys High to Wits School of Architecture, and graduated in 1955.

He would return to Wits Architecture in 1976 as a faculty member in design and construction, and get his PhD along the way. His core area was vernacular architecture, which was Gerald all over: that local is lekker, and good design is solution-led. The best architecture is that which most convincingly solves the simultaneous challenges of function, structure, climate, community, and cost.

By vernacular, he was of course doing “African style” a whole generation before it was cool, or at least before it was cool outside of Broederstroom. But Gerald never followed ideological or artsy fads, nor lived a self-conscious identity as a “creative”.

He was allergic to fashion-led architecture, and punned that Post Modern was in fact “Most Plodden”, whereupon our groans of pain would only encourage him to further “pun-ishment”, for which he would observe: “that’s pa for the course”. Begged to stop already, he might sign off with a winked apology: “To err is human. To forgive, daven.”

Retirement from Wits slowed nothing. Gerald, who always maybe had a bit more tummy than was good for him, was by this time cruising around in coloured trouser-braces (which he made himself) devising and prototyping a completely new form of architectural construction, the “Thin-skin” method.

I won’t bore you with the tech, but it’s worth pausing to get how fundamentally different it is. Houses you know are built by putting lots of little brickies in tall rows and a tiled roof on the top. Thin-skin construction forms walls, floors, ceilings, roofs, etc, all in one, by way of a rebar-reinforced wire mesh framework, thinly daubed over with a concrete skin.

The skin encloses an air gap which provides zero-energy insulation (heat retention and passive cooling) and also serves as moisture barrier in the manner of cavity wall construction.

But it’s not some urban-futuro fantasy. Surfaces are mortared and finished in the standard manner, so when all is said and done, it looks just like “normal”. Various houses in Johannesburg and Cape Town have now been made this way, and you wouldn’t know what’s underneath.

It’s low cost, uses locally sourced materials, and is buildable by unskilled labour, so perhaps you’re thinking what a game-changer this is for housing South Africans and the wider world sustainably and affordably? You’re right.

To this, Gerald was a man of inspiration not institutions. And he is of course no longer around. So that’s where it stands. But the diagrams and technical specifications are all unpatented and free for use, available at https://jmgeraldgordon.wordpress.com/ or via the archive at the Witwatersrand University Architecture and Built Environment Library.

- Adam Gordon is a professor at Aarhus University School of Management, Denmark