Reviews

New novel brings Lazar focus to Linden

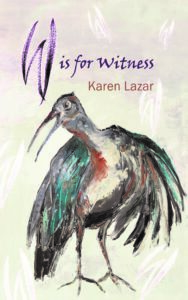

“It all started with a word,” Karen Lazar says of her latest book, W is for Witness. But this book is more than a game of Cluedle or Wordle, though it does have a mystery at its core.

Situated mainly in the Joburg suburb of Linden, it functions on many levels – it jumps spatially from garden to rafter and Jacaranda and back again – and it narrates in many voices, mostly not human but no less observant for being feathered, made of wire, wood, or plastic.

Though the story is mostly set in Linden, it also travels back into history, to 1981, and the famous novel by Nadine Gordimer, July’s People. Gordimer, also Jewish, won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991, and Lazar, an accomplished academic as well as a writer, based her doctoral research on Gordimer’s work.

W is for Witness, Lazar’s third book and her first novel, is intertextual and multilayered, but just in case you’re thinking it’s too academic to read, don’t worry! It’s warm, funny, and accessible – and it must be the first novel set in Linden.

The name “Linden” refers to the Linden tree, which is known for its beauty, strength, and longevity, and Lazar admits to a certain puzzlement at moving to the suburb, known for its gardens and good schools, but also for being a bastion of Afrikaner conservatism and many versions of the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk.

Linden has started diversifying, but not enough, according to Lazar, who points out that its schools are still mostly white. It’s not about racial tallying, she stresses, but the quality of inclusion, and Linden, like any suburb in South Africa, is a microcosm of a macrocosm which hasn’t fulfilled its promises.

So, Lazar is on a mission, like the cyber stalker in the book, to pierce the purple blossoms, chocolate Labradors, and green bubble of this suburb, to wake it out of its self-congratulatory post-apartheid slumber.

“My mandate is not only to reveal Joburg as an un-lit hell born of failed liberation promises and trancuted enactment,” she writes. “Of course, the city is that, too, especially the inner city and urban peripheries, but most of this tale … is based on a self-congratulatory, previously all-white burb. The point of my beak wants to poke through its blithe topsoil to the dystopia beneath.”

It’s a gentle critique, and if you live anywhere near Linden, you’ll recognise the faux culinary sophistication; the rigid educators; the ample-bodied nouveau riche; the hip students; the hard-working professionals with their offices in the garden; even the sometimes passive-aggressive homeless, who remind us that we’re actually living in Joburg.

The book’s chapters are titled according to its many non-human narrators – dominated by the ubiquitous hadeda – who sounds like that “yenta of a meddling auntie”. Rocky, the “chocolate labbie”, is as warm and fluffy as the pony-tailed vet he frequents. But it’s Wire, the electric fence, who reminds us of South Africa’s edgy underbed. “My foe is human,” he says. “Probably a young man who hasn’t eaten in two days and risks electrocution to break the law he hates even more than your walls, your huge cars, and never-ending supply of food deliveries.”

“In narrating through the eyes of a hadeda, a Labrador, a door, a fence, even a restaurant menu, I aim to encourage the reader to see things from a new perspective, to look and listen properly, and to overcome passivity,” Lazar says. Even the pervasive suburban WhatsApp group becomes a metaphor for seeing.

It’s not just seeing that gets turned on its head in this complex tale about a complex city. The book is peppered with poetry which plays on words like “Omelette (Homelette)”; “sturdy; turdy”; “Ditty of Gold”; “seller, bolder, golder”.

Clearly words are as important to Lazar as the city she lives in. Like the proverbial “Karen” – slang for a middle-class white woman who gets things done – Lazar brings a laser – no pun intended – focus to the beautiful contradictions of living in what Antonio Gramsci described as the “interregnum”, in which “the old is dying, and the new cannot be born”.

- Julie Leibowitz is the sub-editor of the SA Jewish Report.