Religion

Not just a story, but a healing journey

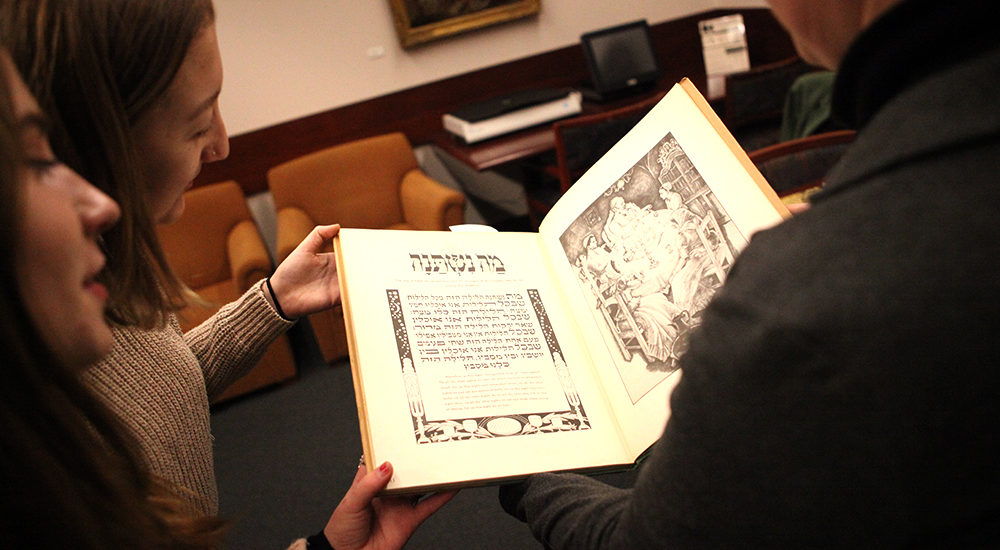

Narrating the tale of the exodus from the Haggadah at the Passover table is at its essence a ritual of storytelling, which psychologists say can be a force for healing, continuity, and sustainability especially during difficult times.

“The motif of sitting around the fire while the leader of the group tells a story to children and adults has deep psychological value,” says psychologist Hanan Bushkin, the owner of the Anxiety and Trauma Clinic.

“Hearing stories allows people to attach themselves to mythical journeys, something we are all hungry for. People have always gravitated towards storytellers. Even if we’ve heard it a million times, we want to hear it again. The predictability of a beginning, middle, and end can give a sense of healing and closure.”

At Pesach, we not only tell the story, we put ourselves in the story, essentially bending time and space. Bushkin says this is a powerful tool.

“By doing this, the story becomes a metaphor for our own lives. As we live out stories of wandering and coming home, we can relate in a very real way to getting through obstacles, the hope of making it to where we want to be, and the resolution that it’s going to be okay. There’s something magical about putting yourself in the role of the characters so that your own individuality resonates with them.

“Human beings are order and pattern-seeking machines,” Bushkin says. “The seder is full of order and structure, with the same pattern repeated year after year. It’s almost like the rhythm of beautiful music that can put you in an hypnotic state. It helps us to transcend the moment and ‘live’ in that space. This is why it’s so engaging year after year, and we want to know what happens next, as if hearing it for the first time.”

Looking at storytelling as a foundation of a nation or family, Bushkin says such “founding narratives” are “are an anchor point to hold onto. There is something very powerful in a ritual that’s so familiar and predictable. It creates a sense of security.”

Thinking about how Jews went to great lengths to have seders while suffering persecution, he says it was “something unwavering that could be held onto. In the same way, wherever we are in the world, at any time in our lives, we can tell the story. This is unifying and comforting, tying us to klal Yisrael. We realise we aren’t alone, even at times like this, under lockdown.”

While Pesach may look different this year, Bushkin emphasises that “our world may be upside down, but our stories are the same. This continuity is very important.”

Professor Joseph (Yossi) Turner, a lecturer in Jewish Thought at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, takes this point even further. “The continuity of Jewish existence is dependent upon the success of Jewish parents in every generation to convey the story of its past to its children. Should it ever happen that the parents no longer have a story to tell; or if the children are no longer interested in hearing the story of their past, the existence of the Jewish people will then come to an end,” he writes.

Bushkin explains that attaching objects or foods to the story, in the way we do with the seder plate, is also a powerful means of transcending the moment and immersing ourselves in the origins of the story. “To hold something like matzah, the same object that was held thousands of years ago when the story played out, is incredible. Tying taste to the story, and using all our senses, almost takes us to another ‘planet’ of experience.”

Clinical psychologist Sarit Swisa says, “The maror, the matzah, the symbols aren’t gimmicks, they give us empathy for what our ancestors endured. It also changes our picture of what liberation is – we leave, but it’s not over. Becoming free isn’t just the act of leaving a confined space, so much more healing needs to happen. By telling the story, we continue the healing.”

“One of things we do in working with trauma,” Swisa says, “is to try to get the person to hold in their mind the image or memory of what happened, while being fully focused on the present. That helps you to heal because it makes you realise that it’s a memory and you won’t forget it, but you have moved on from there. There’s something beautiful about the duality of holding in mind the memory of where we’ve come from, but knowing where we are now.”

Bushkin notes that the vital role children play in the seder is a crucial part of passing the story down from generation to generation. “They aren’t the audience, they are part of the show. In fact, they have a leading role. It’s also wonderful that this is an opportunity for an 85-year-old and a five-year-old to talk about the same story. It transcends age, life experience, and temperament. Having the opportunity to ‘walk the journey’ together is so rare in our modern lives.”

While it has been a traumatic year, Bushkin says Pesach can help us to “transcend the moment” and “reflect on a different reality of hope, identity, and belonging. While the ‘here and now’ might be painful, the story shows we won’t be stuck here forever, and we are all connected to one another,” he says.