Featured Item

Not over till it’s over: more pathogenic COVID-19 variant may arise in future

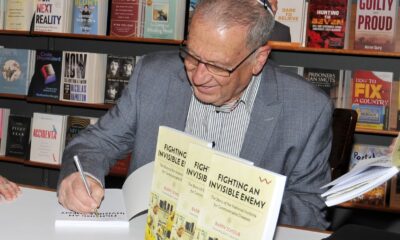

A new COVID-19 variant could cause worse illness than the current predominant Omicron strain, especially in immunosuppressed individuals, according to a new study done by Professor Alex Sigal. It was Sigal’s Durban laboratory that first isolated the Beta variant of COVID-19, and it was also the first to report the Omicron variant “escaping” previous immunity.

Sigal, who was born in Russia, grew up in Israel and Canada, and eventually settled in South Africa, says he conducted the study because it’s “important to know what the possibilities are”, and there’s a “possibility” that the pandemic isn’t over and could become dangerous again.

This could take “a year or more”, he says. At the same time, he thinks vaccines “will probably keep protecting against severe disease, and people should be boosted for the foreseeable future”. He also predicts that “we should expect pandemics every 10 to 20 years or so, based on recent history”.

In the new study, “We looked at what a SARS-CoV-2 virus which has been evolving in one immunosuppressed person is able to do to cells over time,” he says. “We found that the virus shows signs of being more pathogenic since it evolves a greater ability to make cells fuse to each other. This is understandable from the virus’ perspective as it allows the virus to transmit between cells in a way which is much less exposed to our neutralising antibody immune defence.”

The study, released on 24 November, is yet to be peer reviewed and is based solely on laboratory work on samples from one individual. Sigal and other scientists have earlier suggested that variants like Beta and Omicron, both initially identified in southern Africa, may have evolved in immunosuppressed individuals such as those infected with HIV. The long time it takes for these individuals to shake off the disease allows it to mutate and become better at evading antibodies, they say.

South Africa has a large population of immunosuppressed individuals, and Sigal says it’s “likely” that it can be a hotspot for the development of new variants because of this. However, “we cannot be sure if variants come from other places in Africa and are detected here because of better genomic surveillance”.

Sigal’s family came to Israel from the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1974, then moved to the United States and then to Canada “as my father took up academic positions first at UC Irvine and then at the University of Toronto. I went back to Israel to do a short stint in a lab at the Weizmann Institute, and ended up staying for a Masters and PhD. After my PhD, I became interested in virology and took up a position with David Baltimore at Caltech.”

It was after completing his studies at the Weizmann Institute that he travelled to eastern Africa by bicycle, where he witnessed the impact of the HIV epidemic.

“Virology led me to a newly established institute in Durban, South Africa, [formerly K-RITH, now the Africa Health Research Institute or AHRI] as I was particularly interested in the interaction of HIV with other infection,” he says. “There was evidence that evolution of other pathogens can occur in immunosuppression because of poorly controlled HIV infection. This was long before COVID-19. For example, XDR TB was first discovered in South Africa but there was no thinking then – and there isn’t much now – that antiretroviral therapy should be continually supported by a global effort to prevent this.”

He established his laboratory at AHRI in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin, where his interests included neuro-HIV, HIV evolution, and TB. But after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, his group at AHRI pivoted completely to COVID-19 research, and has led the way in many respects.

They established a longitudinal observational cohort to investigate the effects of HIV co-infection on COVID-19 outcomes, and developed virological and serological techniques for isolating and testing variants.

Now, his core research is on understanding the evolution of COVID-19 and its long-term-persistence in the presence and absence of HIV co-infection. He’s particularly interested in variants, long COVID-19,and the effects, antibody neutralisation, and cellular transmission of COVID-19.

“Working on emerging variants is intense,” he says. “Months of work are compressed into days. It aged me mentally and physically.”

If the pandemic becomes dangerous again, “lockdowns aren’t sustainable”, Sigal says. “Boosting [with vaccines], masks, and social distancing should work. What people can do now is a theoretical question – people won’t keep a social distance and wear masks based on a possibility. If it becomes reality, we should be prepared to do it.”

He believes the South African Jewish community “should continue the traditions of striving for and supporting academic excellence and excellence in human endeavour more generally. In my opinion, it’s such traditions that define the community here and globally and not the narrower definitions now being championed by the current crop of politicians in Israel.”