Community

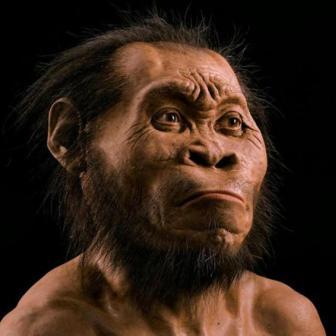

Now ‘real work’ on Homo naledi starts

SUZANNE BELLING

Euphoria’s subsided

The “farewell” took the form of massive concert and picnic organised by the Department of Arts and Culture and the Gauteng Tourism Authority.

In a welcome coincidence, one of South Africa’s most celebrated musicians, singers and song writers Johnny Clegg, was among the artists chosen to perform at the concert – incidentally he is also an anthropologist and a former lecturer at Wits.

It is estimated that over 40 000 people from all walks of life visited the exhibition, more visitors to Maropeng over several months.

The famed Professor Phillip Tobias “would have been over the moon” at the find of this new species of hominin, said Dr Bernard Levinson, a long-standing close friend of the late professor emeritus at Wits and world-acclaimed paleoanthropologist.

Levinson, renowned psychiatrist, said the find at the Cradle of Humankind was “the first time we had encountered another species who bury their dead and sealed them off, indicative of a more advanced culture”.

Scientists had to break into the chamber; the bones were not just lying there, he said.

Levinson likened Tobias’ home to walking into a cave. “There were so many mysteries, every surface was covered by books and manuscripts and work-in-progress and this discovery was made after people had passed through the caves many times.”

He calledthe discovery “a sort of magic. We are suddenly confronted by a culture which had a kind of reverence for its dead. This culture may have had some kind of methodology and belief where the dead were going – some concept of death. It already shows a lot of sophistication.

“The archaeological world is waiting with bated breath for the puzzle to be put together and unravel some of these secrets, including goods they had buried with them to take into the new world.”

Professor Barry Schoub, professor emeritus of virology at Wits, welcomed the widely interpreted big find, but said there was still much to be answered.

“The inaccessibility of the cave begs the question how a relatively primitive hominin dragged corpses for burial in this kind of site rather than conventional burial practices of more advanced hominins including Homo sapiens

“They haven’t dated it yet and this kind of key information is needed to interpret it fully. Paleo-artists are skilled at depicting the appearance from fossil remains. Hominins are distinct from the big apes.”

Schoub said the find reinforced the view that humankind originated from Africa and it would now appear that southern Africa was an even richer source of human ancestral fossil finds than East Africa.

The find of Homo naledi (naledi means “Star”) by Professor Lee Berger, another famed Wits paleoanthropologist and his colleague John Hawks, has – as could be expected – aroused controversy in scientific circles.

Berger has strongly defended his find and conclusions amid some criticism of his classifying naledi as a new genus. Some scientists in the same field have also cast doubt on the “burial theory”, maintaining that Homo naledi did not have the brain capacity to perform such a ritual.

Berger and his team of 60 scientists and associates, pieced together some 1 500 fossil fragments, making up 15 individuals, found in a remote cave.

Homo naledi stood about 1,5 metres high, with heads similar in shape to humans, but smaller.