Featured Item

Oppenheimer’s Jewish facet shines brightly

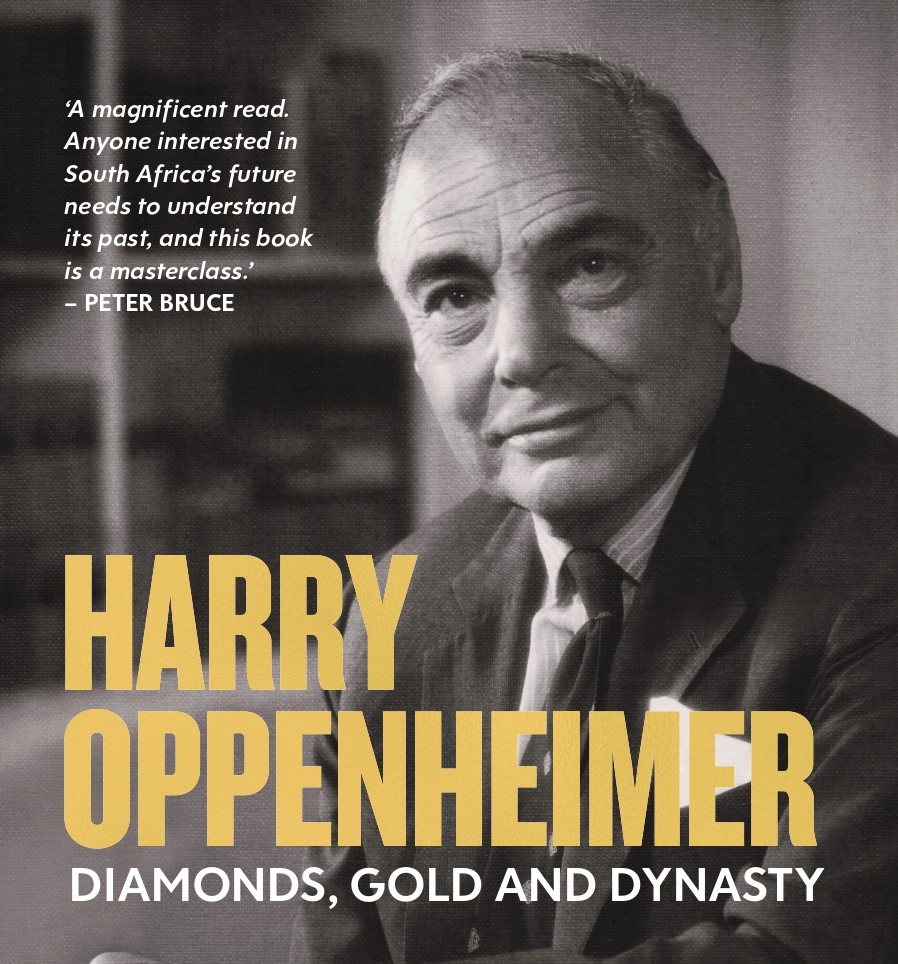

Prominent South African businessman, industrialist, and philanthropist Harry Frederick Oppenheimer – or “HFO” as he was known in the corporate empire of Anglo American and De Beers – may have converted to Anglicanism later in life, but his roots and childhood were deeply Jewish. Researcher, politician, and writer Dr Michael Cardo has delved into this history and more in his new book, Harry Oppenheimer: Diamonds, Gold and Dynasty.

Harry Oppenheimer’s family on his father’s side were German Jews. “His paternal grandfather, Eduard, was a cigar merchant operating just outside of Frankfurt in the second half of the 19th century. He encouraged his six sons to leave Germany. By the mid-1870s, he felt Germany was no longer ‘a country for Jews to live in’,” says Cardo.

“Many of the sons settled in England, found employment with a relative who was a diamond merchant, and spent time on the diamond fields at Kimberley,” says Cardo. “Oppenheimer’s maternal grandparents were Austro-German Jews who settled in England. His parents, Ernest and May Oppenheimer, were married in London in 1906 according to Jewish rites before they settled permanently in Kimberley.

“Their marriage certificate, issued by the West London Synagogue of British Jews, is in the archive at the Brenthurst Library,” says Cardo. “So is Harry Oppenheimer’s bris certificate. He was brissed by Rabbi Harris Isaacs of the Griqualand West Jewish Congregation. For the first seven years of his childhood while he was growing up in Kimberley and attending Kimberley Shul, the contours of his home life were shaped by his parents’ Jewish faith and kinship networks.”

Ernest Oppenheimer was the mayor of Kimberley, but he was forced to flee the town in 1915 after the sinking of the Lusitania in World War I. “I think up until that point, and perhaps even for a few years afterwards, Judaism featured strongly in Oppenheimer’s life. But he was packed off to a public school in England – Charterhouse – at the age of 13, and of course the ethos there was hardly philosemitic.

“Harry began to lose touch with his Jewish roots as a teenager, and so did Ernest Oppenheimer at around that time. The broader political climate – and the cultural environment in which Ernest’s commercial empire evolved after his formation of the Anglo American Corporation in 1917 – steered the dynasty away from the synagogue towards the Anglican Church.

“Ernest eventually converted in the mid-1930s after a series of personal tragedies, most notably the deaths of his wife, May, and his other son, Frank. Then there’s the whole vexed question of whether Harry had a Barmitzvah or not. Successive generations of Oppenheimers came to believe that he would almost certainly have celebrated his Barmitzvah when he turned 13 in 1921.

“In later years, an apocryphal story circulated to the effect that Ernest and May had erected a plaque in Kimberley Shul at the time of Harry’s Barmitzvah, and that in adulthood, having become a Christian, Harry insisted that it be taken down. When the congregation refused, he offered to buy the synagogue, gut it, and rebuild it without the plaque.”

But Cardo says the story is entirely untrue. “There was no such plaque. In any event, the Oppenheimers left Kimberley when Harry was six, and never lived there permanently again. There’s no conclusive evidence that a Barmitzvah took place.”

“Harry Oppenheimer was a towering figure in South African history,” says Cardo. “ He played a major role in South Africa’s 20th-century development. He is so often reduced in public discourse to the personification of ‘white monopoly capital’; in an earlier era, he was demonised by his detractors as [the Jewish caricature] ‘Hoggenheimer’ and the sinister embodiment of ‘die geldmag’ [the money power].”

But Cardo wanted to get to grips with the man behind these caricatures – to give historical context and grapple with him in all his complexity. “The fact that the Oppenheimers gave me unfettered access to all the family papers was a major drawcard. I was able to draw on his letters, diaries, and a cornucopia of other archival material,” he says.

As he reflects in the book, “I felt a bit like one of those diggers who descended on Kimberley in the late 1870s. I set upon the archive as if it were the site of a diamond rush.”

It took him just less than six years to complete the book. “I worked on it part-time since I’m a Democratic Alliance Member of Parliament. The research was intensive because there was so much material to work through and interviews with Oppenheimer’s family members, friends, and business associates.”

Throughout his life, Judaism and Israel remained important to Harry Oppenheimer. “He and [his wife] Bridget [who wasn’t Jewish] visited Israel for the first time in 1968,” says Cardo. “Although the visit was low-key, the diamond-cutting industry attached great significance to it.

“Oppenheimer met David Ben-Gurion – a statesman he ranked alongside Charles de Gaulle in terms of impressiveness – and he subsequently became a steadfast friend to the Israeli nation. He visited Israel on several occasions. His friend, Ludwig Jesselson, a noteworthy Jewish philanthropist who had escaped Nazi Germany, served as his guide on one of these trips. In 1982, they travelled to Lake Tiberius, toured Jerusalem with the mayor, visited Yad Vashem, and enjoyed an hour-long audience with Prime Minister Menachem Begin.”

And in 1986, Harry Oppenheimer opened a facility established by the Israel Diamond Institute in Ramat Gan, which was named in his honour: the Harry Oppenheimer Diamond Museum. “I believe the museum was closed in 2018, but it served as a sort of information centre about all aspects of the global and Israeli diamond industries,” says Cardo.

The book was launched at the South African Jewish Museum (SAJM) even though Oppenheimer had converted. “My parliamentary colleague, Michael Bagraim, suggested that the SAJM would be a fitting space to host an event given Harry’s Jewish roots,” he says. Cardo believes this history is an important part of Oppenheimer’s story.

“It was interesting for me to discover how, in the 1950s, when Harry Oppenheimer was a Member of Parliament for the opposition United Party, the National Party government weaponised antisemitism against him even though he had long since converted to Anglicanism,” says Cardo. “Harry came to be depicted as ‘Hoggenheimer’ in the Afrikaner nationalist press, just as his father had been two decades previously. This antisemitic caricature symbolised British-Jewish imperialism and predatory mining-finance capital.

“The Jew-baiting reverberated through the House of Assembly,” says Cardo. “At that moment, the figure of ‘Hoggenheimer’ – much like the ogre of ‘white monopoly capital’ decades later – rallied the Afrikaner nation against a common enemy. This reinforces how malleable and persistent antisemitic attitudes can be. Antisemitism lurks below the surface in many societies, including South Africa, so there’s always a need for vigilance.”

- The book was launched at the SAJM on 26 June. Small Jewish Communities Association Rabbi Moshe Silberhaft discussed the impact of the Oppenheimer family legacy on the Kimberley Jewish community.