Parshot/Festivals

Pesach, Easter, and Ramadan – we’re all connected

This year, Pesach and Easter fall on the same weekend. It’s also during the month of Ramadan. So the three Abrahamic faiths are all marking holy time together. What do they have in common, what’s different, and what should we take away from this coinciding of dates?

First, let’s start with the mood. Ramadan is serious – it’s daily fasting, introspection, striving with oneself to be a better person. Think an “Elul and high holy days” mood. Easter seems to outsiders to be upbeat, with the Easter egg hunts and all, but actually, it marks the close of the 40-day Lent period, a time like Ramadan of abstinence and repentance. Even though it’s called “Good Friday”, the first day of Easter is actually the day Christians commemorate Jesus’s death. And Easter Sunday, when it’s believed that Jesus rose again, isn’t marked with celebration and lots of food and wine, it’s actually spent in Church with lots of meaningful prayer time.

Here’s where Judaism differs to its siblings this time around. Pesach is upbeat and celebratory right the way through because we were taken out from slavery and rescued from the oppression of Pharoah. We have seder night, tell stories, and fill up on good food and wine, (lots of it, four cups for everyone), and spend the week on semi-holiday.

Speaking of food, there are some important connections and differences here too. Ramadan is a daytime fast, but come sundown, there’s lots to eat. And it starts traditionally with dates. Dates are a symbol of springtime and many Jews, especially Sefardim, include dates in their traditional charoset recipes. Christians, as we said, get Easter eggs, which sound a lot more fun than a boiled egg in salt water (which is surprisingly tasty after a long chunk of seder reading and easier on the palette than the not-so-tasty Hillel sandwich), but there’s of course that common egg-theme of spring, hope, and rebirth to both. They get chocolate bunnies, which is pretty cool, and neither the Muslims nor the Jews have rabbits in sight, but it’s the Jews and the Muslims that have the most food restriction – for Muslims, a month of fasting, and for us, no pizza or bagels and instead perforated cardboard for a week. Lechem oni, the bread of affliction. Compensated by the prize for the afikomen, which seems to rise radically in Pesach-inflation each year. And then there’s the year that Uncle Abe forgot where he hid the matzah, and everyone got roped into the hunt. Reminiscent of Easter egg hunts after all.

Which brings us to the hunt for chameitz. On the night before seder night, Jews get out their candles, feathers, and spoons and look for the last bits of chameitz that have been craftily hid in the kitchen and lounge. For kids, this is the best part, but here’s a big tip. Make a note of where you hid those pesky pieces of chameitz. Inevitably, there’s that last-minute panic when nine out of 10 pieces are found and no-one remembers where the 10th is. The big difference to an Easter egg hunt is that we don’t get to eat those found pieces of chameitz. We throw them on the braai the next morning with the accompanying Aramaic declaration of annulment, and head off to get the seder ready.

At the seder, we re-tell the story of the Exodus in an interesting and roundabout way with songs and tangential midrashim about how Rabbi Akiva thinks it wasn’t just 10 but 50 plagues, and how Rabbi Elazar’s hair went grey. But Islam is equally interested in the events of the Exodus. The Qur’an mentions Moses more than any other prophet (by the way, Moses isn’t mentioned at all in the telling of the Exodus in the Haggadah) and has multiple narratives of his story including repeated descriptions of the Exodus from Egypt and the wanderings of the Israelites in the desert. And even though there’s much debate about this among scholars, many believe that Jesus’s Last Supper was, in fact, a Pesach seder.

So many interconnecting similarities and differences remind us that we’re all children of Avraham, and this month especially, we should find ways to connect to each other and wish blessings for the holy days ahead.

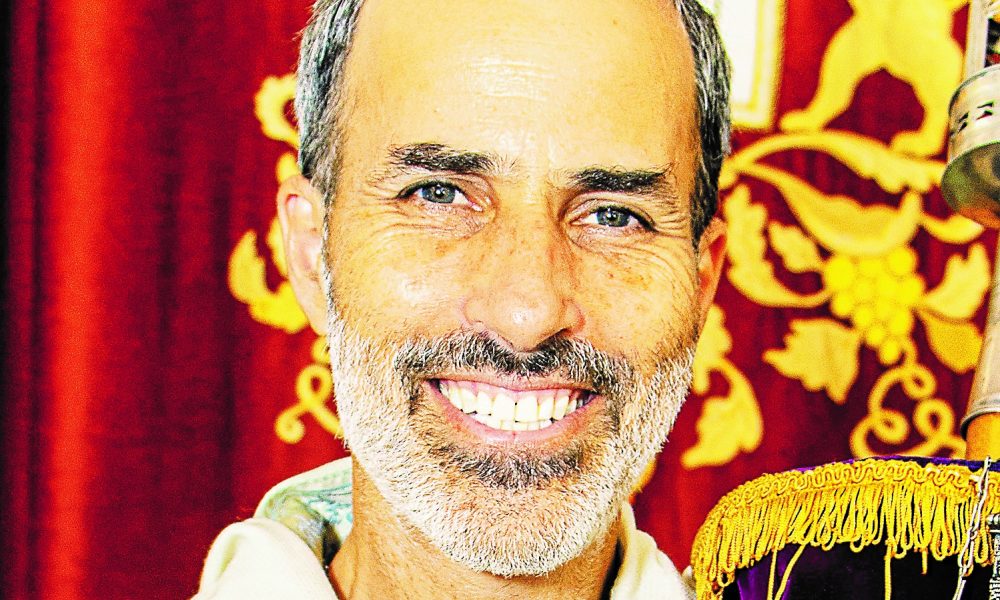

- Rabbi Greg Alexander is part of the rabbinic team at the Cape Town Progressive Jewish Congregation.

Carolyn Smollan

April 17, 2022 at 5:24 pm

Beautiful message Rabbi Greg, You always have wonderful words to share.

Thank you.