News

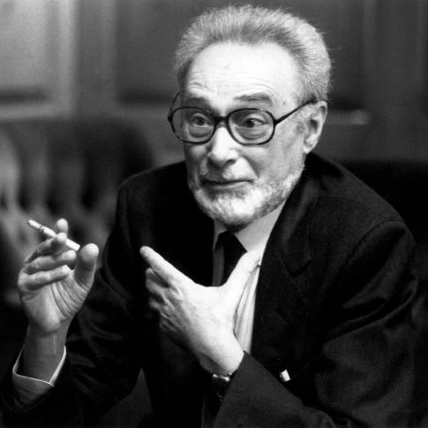

Primo Levi: the unbearable burden of bearing witness

MIRAH LANGER

The focus of his talk was Italian Jewish chemist Primo Levi, who became famous for his writings about his experiences as a prisoner in Auschwitz.

Barenghi, a professor of contemporary Italian literature at the University of Milano-Bicocca, was lecturing in South Africa as part of recent commemorations of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January.

Levi, born in Turin in 1919, initially joined a partisan group when World War II broke out. However, the group was infiltrated, and Levi was sent first to a labour camp, and then to Auschwitz. He survived an 11-month stay there before being liberated on 18 January 1945.

In the ensuing years, Levi published a number of books, including If This Is a Man (1947), The Periodic Table (1975), and The Drowned and the Saved (1986). His works have become recognised as seminal texts in exploring the Holocaust experience.

In 1987, Levi died after falling down a landing in his apartment building. His death was ruled a suicide.

Barenghi proposed in his lecture, attended by representatives of the Italian embassy, that what elevated Levi’s testimony was his reflection on the difficulties of bearing witness.

For example, many camp survivors, like Levi, struggled with how after their Holocaust experiences, time no longer seemed to flow normally.

“A barbed-wire fence, similar to the one at the death camp that separated the inside space from the outside now separate[d] the past from the present,” explained Barenghi to the packed audience.

This meant that for Levi, even though he had survived, he often felt “closer to the dead than to the living”.

Sometimes, the pull of the past was so strong, “the survivors [were] haunted by the fear that the liberation itself [was] a dream, and that they will soon wake up in the camp again”.

At other moments, Levi expressed the survivors’ distress that the atrocities experienced were so unparalleled, those who listened would not believe them.

“My listeners do not follow me. In fact, they are completely indifferent… A desolating grief now rises in me,” quoted the professor from Levi’s writing.

In addition, explained Barenghi, it was sometimes difficult even for survivors to accept the veracity of their own memories.

He cited, as an example, Levi’s declaration that, “Today, this very day, as I sit at a table and write, I myself am not convinced that these things really happened.”

The professor also suggested that when it came to Levi’s writings, what he elected not to write about was as crucial as what he did choose to include.

“His testimony is based on his awareness of the need to be selective with information. In order to actually say something, you have to give up all thought of saying everything,” said Barenghi.

The professor quoted from Levi’s account of his journey to Auschwitz, where he declared, “Many things were then said and done among us; but of these it is better that no memory remain.”

Barenghi added that alongside moments when Levi explicitly stated that he was leaving out information, there were other omissions that Levi never overtly discussed.

For example, in If This Is a Man, “although death looms over the whole narration as a huge, dark shadow, the only direct depiction of a dying man occurs in the last chapter”, he noted.

By contrast, the violence committed against prisoners was frequently referenced in Levi’s work – showing his focus on detailing observations of human behaviour.

Levi’s writing could be traced across two phases, proposed Barenghi.

In the first stage, Levi’s style was linked to the Italian term vertiginosamente – a concept linked to vertigo – with connotations of “something frenetic, dizzying, whirling”.

As such, “in this first phase, then, the narration originates from instinct and impulse, from a need to let off steam”, posited Barenghi.

Levi’s second phase became more closely linked to his profession as a chemist. As Levi himself described it, he took on the role of a writer “who weighs and divides, measures, and judges on solid evidence, and does his best to respond to the whys”.

“His purpose is now to distil knowledge from horror,” Barenghi said about the shift.

No longer did Levi’s testimony consist of “the simple preservation of the past”. Instead, his accounts were now styled to function “as a warning for our common future which concerns everybody”.

Levi came to the hypothesis that the roots of genocide could be located in the widespread – although often latent – belief that “every stranger is an enemy”.

Nevertheless, he chose to uphold the possibility that this belief could be challenged, and a common humanity asserted instead.

As such, suggested Barenghi, Levi’s work came to serve as a proposal for the acceptance of the other “not as a gracious granting, but as the foundation of one’s own humanity. Nobody is human alone.”

“Here… lies Primo Levi’s most precious legacy,” he concluded.

Alida Poeti

March 7, 2019 at 12:47 pm

‘Excellent article with which I concur completely. Only when we can truly say that in our minds we do not see anyone as a lesser being or a potential enemy for whatever reason, can we aspire to be human in its highest sense. Unfortunately we tend to excuse ourselves by claiming that we are only "humane" thus weak and fearful of those who are deemed to threaten the status quo. Levi recognized human weakness and implores us question our values, our beliefs and embrace ‘otherness".

I am not a religious person but believe that literature consumed by choice and in private has the power to move hearts as much as – if not more than – a most preaching.

Keep me informed of any articles you publish that relate to Jewish literary studies.’