World

Salvaged Soviet-Yiddish songs nominated for a Grammy

PENNY SCHWARTZ

On the High Mountain, written by Veli Shargorodskii about the war experience from 1943 to 1944, ends with the words, “Germany is in trouble, Hitler is kaput!”

The satirical song was among hundreds collected during the war by Moisei Beregovsky (1892-1961), a Russian-Jewish ethnomusicologist and Yiddish scholar. Beregovsky led a team of colleagues and volunteers for the Kiev Cabinet for Jewish Culture, a department of the Ukrainian Academy of Science.

Beregovsky and his colleague, Ruvim Lerner (1912-1972), planned to publish an anthology of the collected songs, a continuation of Beregovsky’s earlier groundbreaking work to preserve Jewish folk songs and Yiddish and klezmer music.

But after the war, their hope was dealt the cruel blow of Stalin’s vicious anti-Semitism. In 1950, Beregovsky was arrested, convicted of Jewish nationalism, and jailed for five years. Soviet authorities confiscated his monumental collection of music from the war years, and he and Lerner died believing their work had been destroyed.

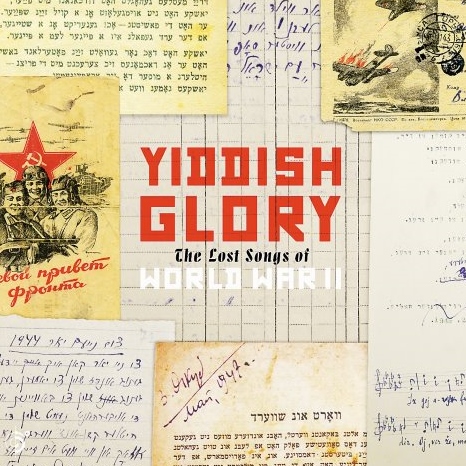

Now, following an unimaginable series of unlikely events, these rare and revealing songs, presumed lost to history, were rediscovered and have been brought back to life in Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II. (Six Degrees Records).

The recording has been nominated for a Grammy Award among five finalists in the world music category.

The winners will be announced on 10 February in a live broadcast from the Staples Center in Los Angeles.

Yiddish Glory is among the fewer than a handful of Yiddish-language recordings to have been honoured by the Recording Academy. The Klezmatics scored a Grammy in 2007 for best contemporary/world music album; at the time, awards in world music were divided between traditional and contemporary. In 1982, the Klezmorim were nominated for best ethnic album.

Yiddish Glory represents a multi-year, ambitious undertaking led by Anna Shternshis, a professor and scholar of Soviet and Yiddish culture at the University of Toronto, and Pavel Lion, a Russian-born musician and scholar of Yiddish literature who goes by the pseudonym Psoy Korolenko.

Produced by Dan Rosenberg, the music was arranged by Sergei Erdenko, acclaimed as Russia’s greatest living Roma violinist.

They gathered an all-star band including Juno Award-winning vocalist Sophie Milman, a Jewish jazz performer based in Canada who was born in Russia.

The recording, hailed on scores of best-of-2018 album lists, includes 18 tracks. The extensive liner notes include lyrics for all the songs in English and Russian translation, as well as fascinating background material and archival images.

Jews from all walks of life wrote the first-person lyrics – from Jewish Red Army soldiers and refugees, to victims and survivors of Ukrainian ghettos. They ring with defiance, revenge, love, hope, and Jewish humour.

Shternshis was stunned by the Grammy nomination.

“Given the whole history, where it all started… it’s unbelievable,” she told JTA in a phone interview.

It is an extraordinary tribute to Beregovsky and his colleagues, who risked their lives and suffered consequences for their dedication to Jewish culture and memory, said Shternshis, the director of the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies.

Shternshis learned about the material by chance in the early 2000s, when she was doing research at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kiev, where librarians discovered Beregovsky’s collection in unmarked boxes in the 1990s.

She recognised the find as a historical and cultural treasure trove.

“I was shocked on so many levels,” said Shternshis, recalling when she delved into thousands of pages of yellowed, sometimes tattered paper with typed or handwritten lyrics. Steeped in the history of Russian Holocaust literature and the music of the region, she was incredulous that she didn’t recognise a single song.

The songs were notably distinct from music from Vilna, Warsaw, and Lodz, with references to Stalin and the Soviet Union.

“The music had no parallels,” Shternshis said.

Only about 10% of the songs included musical notation. Some referenced or gave hints of popular tunes of the times.

After Korolenko immersed himself in the material, a process he described as “musical archaeology,” he took a leap of faith to compose or adapt melodies, sometimes drawing on popular or folk music.

On the High Mountain, the first song, leads with the soulful call of David Buchbinder’s trumpet. The lyrics are a nod to an old Yiddish counting riddle, and Korolenko’s lively melody recalls that famous folk tune.

Several songs offer ground-level, vivid descriptions of the massacres in Babi Yar, Tulchin, and Pechora in Ukraine.

Mames Gruv (My Mother’s Grave) is a child mourning the death of his mother sung by Isaac Rosenberg, Shternshis’ son, who was 11 at the time of the recording. He is beyond thrilled that he’ll be attending the Grammys, said Shternshis, who has to miss the ceremony.

The fifth cut, Mayn Pulemyot (My Machine Gun), describes a Jewish soldier’s pride at using his machine gun to kill German soldiers. Shelakhmones Hitlern (Purim Gifts for Hitler) strikes a lighter note in comparing Hitler with Haman, the villain of the Jewish holiday of Purim.

Milman brings smooth, sultry vocals to Kazakhstan, a cabaret-style ode of gratitude to the land where a quarter-million Jewish refugees survived. It’s the only song on the album in which Erdenko composed a new tune, combining Roma, Yiddish, and Romanian styles. The song is deeply personal for Milman, whose grandmother survived as a Soviet Jewish refugee in Kazakhstan, and for Erdenko, as a tribute to the Roma who were also victims of the Holocaust.

Rosenberg, the project’s producer, often thinks about the composers who took pen to paper, many of whom were killed during the Holocaust.

“They felt it was important to try to share their personal stories, their warnings about fascism, and their dreams for a better future in the faint hope that these stories would someday be heard,” he wrote in an email.