Lifestyle

Sephardi cliffhangers built my career, says Zimler

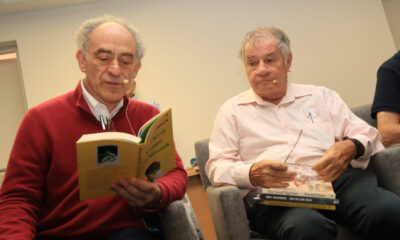

Bestselling international novelist Richard Zimler, whose most popular work is a series of novels about a Portuguese-Jewish family, will be attending the Jewish Literary Festival on 28 April. The SA Jewish Report speaks to him.

How would you describe your genre?

Mostly literary and historical fiction. I have a series of independent novels about different generations of a Portuguese-Jewish family, the Zarcos. The books aren’t in any order, but I love having nearly invisible links between them. The narratives take place in different places and time periods. The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon takes place in Portugal in the early 16th century during an antisemitic riot. My latest novel, The Incandescent Threads, explores the lives of two descendants of the narrator of The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon.

What inspired you to write books about the Sephardi Jews of Portugal?

When I first moved to Portugal in 1990, I discovered the Lisbon Massacre of 1506, in which 2 000 forcibly converted Jews were murdered and burnt in the city’s main square. When I asked my Portuguese friends what they knew about it, all of them replied, “What massacre? There was never any massacre!” It had been eliminated from official history books and school manuals! I felt obliged to force people to recognise the devastation it caused and give a voice to people who were forcibly silenced.

How close are your books to the facts of Jewish life in those days?

Very close. I research my books thoroughly to get the details right. For instance, when I was preparing to write Guardian of the Dawn, which is set in Goa (in India) in the early 17th century, I researched daily life in that Portuguese colony over many months.

When you wrote your first of this series of books on Sephardi Jews, you battled to find a publisher. What happened?

When I finished The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon, my agent in New York started submitting it to publishers in America. At the end of two years, they had all turned it down – 24 publishers in all. They all said virtually the same thing, it’s a wonderful novel, exciting and well-written, but it will never sell. I became depressed, of course. The book took me a year to research and two years to write. A crazy idea saved me: why not show it to a Portuguese publisher? The first publisher to whom I sent it said it was the best novel she’d read in years. In many ways, I owe my career to that Portuguese publisher.

The book became a number-one bestseller in Portugal. Why?

Portuguese Jewish history and culture were largely taboo in Portugal from 1497, when all the Jews were forcibly converted to Christianity, until the democratic revolution of 1974. That’s almost five centuries of silence, misinformation, and persecution. So when my book was published in 1996, for the first time in several centuries, people felt free to learn about a hidden aspect of their country’s history. About 18 years ago, a monument to the forcibly converted Jews who were murdered in April of 1506 was commissioned and erected in the city’s main square. People at the Lisbon City Hall have told me that without The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon, that monument would never have been built.

What do you believe their appeal is?

A great many readers agree with me that it’s important to read about people who have had their voices stolen and who have been eliminated from official histories. I also try to tell a captivating, realistic, and impassioned story, one that will engage readers on different levels and stir deep emotions. I often get emails from people telling me how they cried at certain points in my books. And at other points, they grew enraged. Deep emotions mean that a novel is connecting strongly with a person and maybe even changing his or her life.

Can you describe the Portuguese Jewish community of today.

There are three communities: in Lisbon, Porto, and a small town in the northeast mountains called Belmonte. They’ve grown quite a lot in recent years because of a government programme that has allowed people who can prove Portuguese-Jewish ancestry to obtain Portuguese nationality.

How do they compare to the communities in your novels?

In my novels such as Hunting Midnight and Guardian of the Dawn, the Jews have already been forced to convert to Christianity. They could be arrested and imprisoned for something as simple as whispering a Hebrew prayer in public or washing their bedsheets on Friday before the Sabbath.

How did you put these books together?

While I’m doing my research, ideas about the book’s characters and story come up. When I start writing, I usually know what’s going to happen in the first chapter, but after that, I have no idea. That leaves room for surprises, improvisation, and moments of revelation. In my experience, authors who plan their whole novel from the beginning tend to write narratives that are contrived and obvious, and I want to avoid that. I write for two or three years or more until I’m happy with the book. Then I go back to the beginning and do a careful re-write.

Why do you believe writing this series is so important?

Most readers realise that it’s a terrible injustice for minorities and others to be excluded from official histories. For instance, in the country where I grew up, the United States, Native Americans were generally excluded from our studies in American history.

Why are you keen to participate in the Jewish Literary Festival?

It’s such a blessing to be able to have my books read by people in different countries and for them to tell me about their reactions to my books. On a personal note, my husband, who was from Mozambique, did all his university studies, including his PhD, at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. He has many fond memories, and has told me hundreds of stories about his life there.