Lifestyle

The hidden, humbling history of the Litvaks

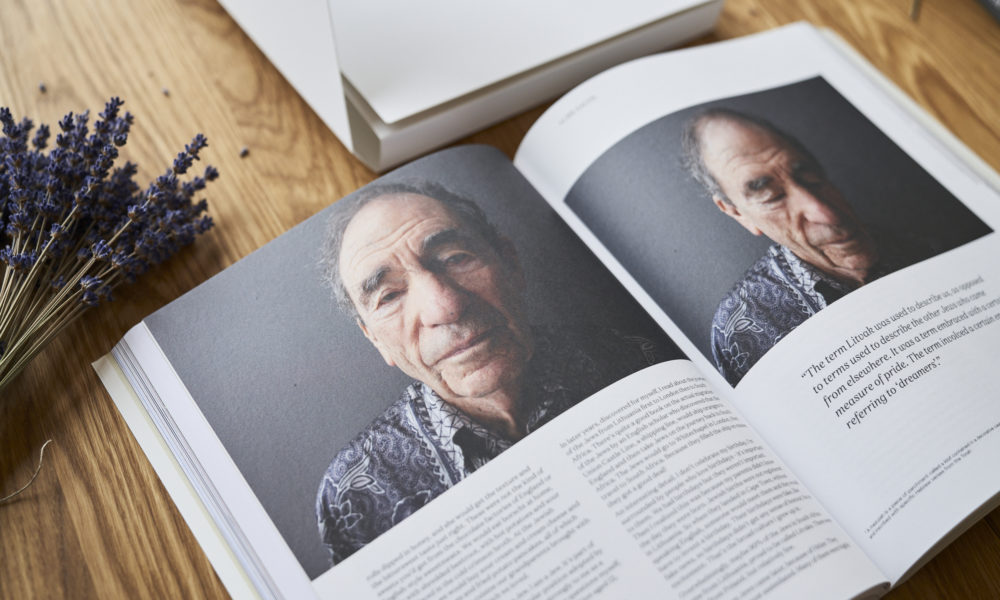

Kęstutis Pikūnas put together a beautiful coffee table book called ‘Passport – The Litvaks’ about the Jews of Lithuania. Being Lithuanian and having grown up there, he knew nothing about Litvaks beforehand. The SA Jewish Report asked him about his experience.

How did this project come about, and do you have a Litvak background?

When I first started writing these Passports, my goal was to present Lithuania in an annual English publication for a foreign audience.

Being Lithuanian and having lived abroad for many years, I wanted to tell the story of Lithuania through its people from the best possible angle. This ambition came from bitter personal experience and the fact that many people identified me as a foreigner who came from a culturally and economically poor country. It triggered a sense of inferiority and frustration, leading me to try to prove everyone wrong.

Little did I know that as I interviewed luminaries, I learnt humbling life lessons. I realised how little I knew about the history of my homeland and how selective and superficial my approach was. This was the beginning of my journey.

I don’t have a Litvak background and when I started the project, I didn’t plan to dedicate one whole publication to the Litvaks. This was because I knew very little (or close to nothing) about Litvak culture, heritage, and history.

I was born at the time when Lithuania was still under the Soviet regime, so we didn’t learn about it at school, nor did my parents talk about it at home.

When I was compiling the second volume, I met Professor Irena Veisaitė, who was among the few Jewish survivors of the Holocaust in Lithuania. Meeting her was an eye-opener.

Hearing her extraordinary story of survival and courage, I was left with countless unsettling questions. How come I had only learnt about this now? Why was my perception so superficial for so many years? Where does this disinterest and denial come from?

This initial conversation led to a dear friendship and further discoveries. After interviewing her for the second volume, which also features an interview with South African cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro (known as Zapiro) and Litvak businessman Eli Broad, it was clear to me that the third volume would be dedicated to the Litvaks.

What did you expect to learn from the project?

I had way more questions than answers. As I learnt more, I felt a deep sense of shame about the massacres and local collaborators.

To this day, I find it hard to comprehend how, in this modern day and age, we still choose to turn a blind eye to the uncomfortable truth, trying to forget rather than talk openly about it.

It always puzzled me. We all know that Jews lived in Lithuania for hundreds of years. They created, built, and loved together. There are plenty of signs all across Lithuania of that. But I understand that realisation comes gradually. This is what this experience has taught me.

What were you trying to achieve and why?

I wanted to induce empathy and honest dialogue. I believe storytelling is a powerful tool, and it can work miracles if it captures the reader’s attention on a personal level.

I’m happy that I had an opportunity to record and perpetuate what I consider an inseparable part of Lithuanian history.

A friend of mine (I had no idea he was Jewish), whom I interviewed, said, “History is made up of facts, but treating these facts selectively, choosing what feels acceptable and familiar but ignoring anything that may be unpleasant, is foolish. This road leads to nowhere, and often results in hostility.”

I believe that knowing history through its dry facts and figures is one thing, but being able to understand the events and reasons why and how it all happened is another.

Another important detail which is important to mention is that I didn’t have to do this book, I chose to do it. It was never my intention to invent something new, quite the opposite. I wanted to feel it, discover it, and “walk a mile in someone else’s shoes”. And I don’t regret a single minute of it.

What were the stories/anecdotes that stood out for you and why?

It would be hard to pick out one story that stood out the most while compiling this publication as they all are personal and delicate. Probably the reaction of my peers surprised me most as I was keen to learn what my family and friends knew about Lithuanian Jews and the history of Lithuanian Jewry. To this day, there are so many ridiculous superstitions, myths, and twisted narratives about the Jews. I simply don’t get it. As for anecdotes, there aren’t that many, and they are far from funny.

What were the most emotionally tough parts to deal with?

Quite a few. Being at murder sites and talking to Holocaust survivors about their experiences moved me immensely. It would be impossible to describe that feeling in words as it’s utterly incomprehensible how this could have happened. Just standing there next to a pit, or simply looking into a person’s eyes who witnessed the atrocities without saying a word, these silent moments speak volumes to me.

Was there anything uplifting and inspiring in the process?

The courage of those who stayed true to human values. Those who resisted, and risked their own lives to save their neighbours or even a stranger. Their stories and testimonies will stay with me for the rest of my life. Of course, becoming friends with those who contributed and those whom I interviewed for this publication is another rewarding experience.

What were your impressions of the South African Litvaks you spoke to?

I only had the chance to interview Robbie Brozin, who later introduced me to Justice Albie Sachs. Each of their stories are unique and valuable. I have to admit that even in my wildest dreams, I wouldn’t have thought that I would ever have the chance not only to interview them, but make friends with them. This is very important. I keep in touch with them and our friendship is dear to me.

How did you deal with the South African aspect of the book?

The story of South African Jews is unique. Not many people know that more than 90% of the Jews in South Africa came from Lithuania. Right before the pandemic, I was planning to go to South Africa together with the photographer and spend some time there documenting. As strong and insightful as Albie and Robbie’s interviews are, I believe it’s just the tip of the iceberg. I hope that in the near future it will be possible to travel again and continue what has been started.

What was the reason for putting Sachs on the cover?

Our first conversation lasted for maybe more than three hours and prior to that, we simply agreed to talk, without a set list of questions or any further commitments. I’m happy that Sachs kindly agreed to our talk being transcribed, edited, and published. He embodies everything that this publication is about. I could go on and on about the reasons why Albie is on the cover, but I believe that G-d is in the details. And I have to say that Steve Gordon, a dear friend of Albie, took fantastic photographs.

On completion of this book, what have you learnt about the Litvaks?

An awful lot! I quote Meryl Frank, a Litvak from the United States, whom I also interviewed: “The worst thing a person can do to another is to ignore them, to fail to see them, and erase them from history. I have seen a change in Lithuania over the 15 years I’ve been visiting the city of Vilnius [Vilna]. I believe that with the passage of time and the recognition of history, there is a possibility for building bridges.” I honestly believe that there is no better time than now to reach out for each other’s hand. The truth has the power to liberate.

What would you want those who read your book to learn or understand?

This is probably the hardest questions of all, because while compiling this book, I was often asked questions like: “Why is this important?”; “Why should I care about the past?”; “Why do you care?” and so on and so forth. I think there’s no right answer to this question. I truly hope that the reader will take away a sense of empathy and compassion.

Why do you believe this is an important book, and who is it important for?

The book is relevant to everyone, and it’s especially important for us ethnic Lithuanians, Lithuanian Jews, and Litvaks. It’s a genuine invitation to review and, hopefully, renew the relationship.

Carole smollan

June 17, 2021 at 2:34 pm

Where can one order this book in UK PLEASE

RAMI REZNIK

June 18, 2021 at 12:44 pm

Very impressive interview.