Jewish News

The ‘Imperial Tour’ that cemented the Jewish Commonwealth

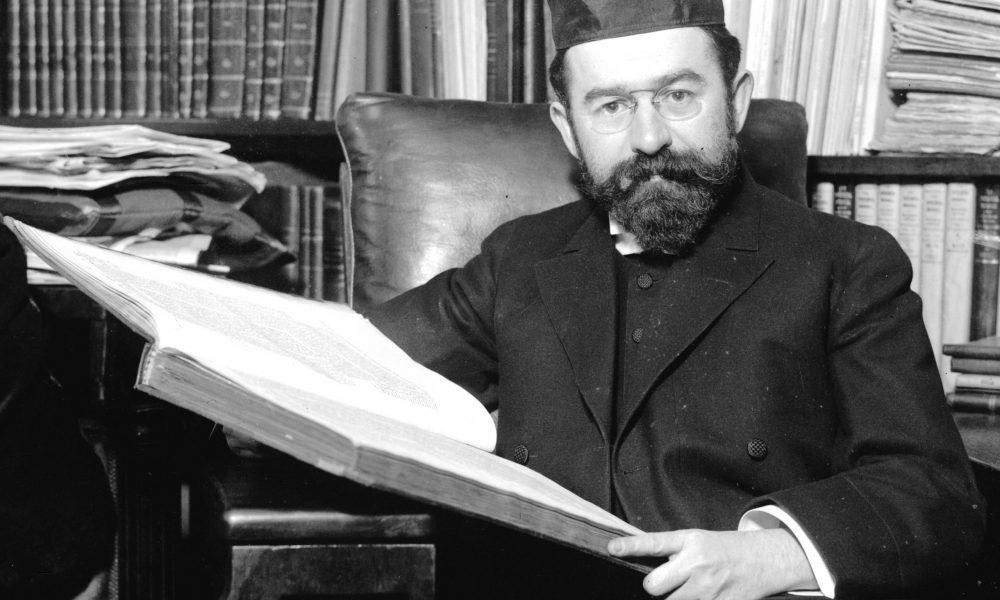

Exactly one century ago the chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the British Empire, Dr Joseph Hertz, arrived in South Africa on the first leg of a global tour which lasted almost a year.

Arriving in South Africa on 27 October 1920, he spent more than three months in the country. He then went on to visit significant Jewish communities in other dominions: Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. The entire tour covered 42 communities and 40 000 miles (64 000km).

Hertz, who became chief rabbi in 1913, got the idea of conducting a tour after seeing the Prince of Wales’ visit to Canada following World War I. He wanted to do something similar, and visit smaller communities, saying he was “enthused to come into personal touch with the distant communities under my ecclesiastical jurisdiction”.

Earlier on in his career, he had served as rabbi to the Witwatersrand Old Hebrew Congregation in Johannesburg (from 1898 to 1911). During this time, he publicly challenged the Kruger regime, and supported the administration of Lord Alfred Milner, who recommended him to Lord Rothschild for the vacant post of chief rabbi of the British Empire.

Hertz set sail from the United Kingdom (UK) on 8 October 1920, and reached South Africa almost three weeks later. The tour was branded a “pastoral tour”, but the agenda was also to raise £1 million for Jewish education as a memorial for those who had died in the Great War. Indeed, a letter in the United Synagogue archives reveals correspondence from a man in South Africa to Hertz, aggressive in tone, asking whether the trip was for the purpose of Jewish pastoral care or if it was to raise money for the Jewish War Memorial.

The chief rabbi replied, “Let me assure you, dear Mr Ehrlich, that I am coming to South Africa on a purely Jewish mission. It is true that there will be an accompanying appeal for the Jewish War Memorial, but I regret the ‘war’ part of it as much as you do.”

South African Jewry had a population of 66 000 at the time. Hertz travelled throughout the country, covering 5 000 miles (8 000km) by railway. His first public engagement was a sermon at the Great Synagogue in Cape Town on Shabbat 30 October 1920. He was impressed by the shul, describing it as “the largest and most impressive Jewish house of worship in the empire”.

He also warmed to its minister, Rev A P Bender, whom he said was “a most popular and respected figure, not only in the Jewish, but also in the general life, of [the] Cape Colony”. Bender was a part-time professor of Hebrew at Cape Town University. In the following days, the chief rabbi was given a banquet at City Hall, delivered a sermon at New Synagogue, and attended a reception of the Cape Town University J-Soc.

Hertz then travelled to Kimberley, where the community dated back to 1869. It was there that he sounded a warning about assimilation. In a sermon, he said that there had been “too much drifting in religious life”, and the perils faced by South African Jewry were the same as those confronting Jewish communities in England, Australia, and Canada.

After a trip to Bloemfontein, which brought back memories of consecrating the synagogue in 1902, Hertz moved on to Johannesburg. In this city, he received a rapturous welcome, with crowds waiting for his arrival at the railway station.

The Sunday Times reported afterwards, “There can be no doubt of the warmth of his welcome from his old congregation. He comes here not only as the high priest of English Jewry, but as an old friend who through long years of unselfish work among us endeared himself equally to Jew and Gentile.”

The next stop was Pretoria, where Prime Minister Jan Smuts gave a speech praising the contribution of the Jewish community and looking forward to it flourishing in the future. In his remarks at the reception, Smuts declared, “The Jews in South Africa are welcomed in every walk of life, and have achieved the greatest successes. Nobody grudges them their success because they deserve it. Let them bring their resources and talents to this country.”

At his next destination, Bulawayo in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), he said he found “Jewish hearts throbbing with enthusiasm for all forms of Jewish endeavour”. Hertz spent a final few weeks in South Africa visiting Pietermaritzburg, Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, and Oudtshoorn.

One of the things Hertz noticed about the Jews of South Africa was how charitable they were – a characteristic still identifiable today (even among those who now live in Israel, the United States, and the UK). He was struck by the care shown in the orphanages in Cape Town and Johannesburg. He was also impressed by the community’s raising of £450 000 for the War Memorial Fund, remarking that it was “a record of generosity that surpasses even that of American Jews”.

Afterwards, Hertz wrote about the success of the visit. “Thank G-d it has been justified by the results, which in view of the extraordinary financial position prevailing in this country, are very gratifying indeed.”

After this ground breaking world trip lasting almost 11 months, Hertz arrived back at Southampton on 30 August 1921, and had a private audience with King George V at Buckingham Palace in November.

The “Imperial Tour” is one of the things Hertz remains most famous for, along with his commentary on the Chumash. It solidified the bonds between the UK and her then dominions, and gave him and his office profile on the world stage.

A century on, the historic ties endure. The sun may have set on the British empire but, 100 years after Hertz’s landmark tour, the ties between Jewish communities across the Commonwealth remain strong.

- Zaki Cooper is on the diplomatic advisory board of the Commonwealth Jewish Council.