Banner

The Jewish explorer who befriended Shaka Zulu

Shaka Zulu was a formidable figure, but this didn’t deter Jewish explorer and traveller Nathaniel Isaacs from getting to know him and even fighting alongside him in the early 1800s. In return for his support, Shaka gave him large tracts of land, including what’s now Durban.

Isaacs also recorded in his diary at the time that he offered the members of the Zulu tribe the quintessential Jewish remedy of chicken soup when they were ill.

South African Jewish community leader Benji Shulman stumbled across Isaacs’ story and a letter from Shaka to Isaacs about his “reward” while researching Jewish history in South Africa.

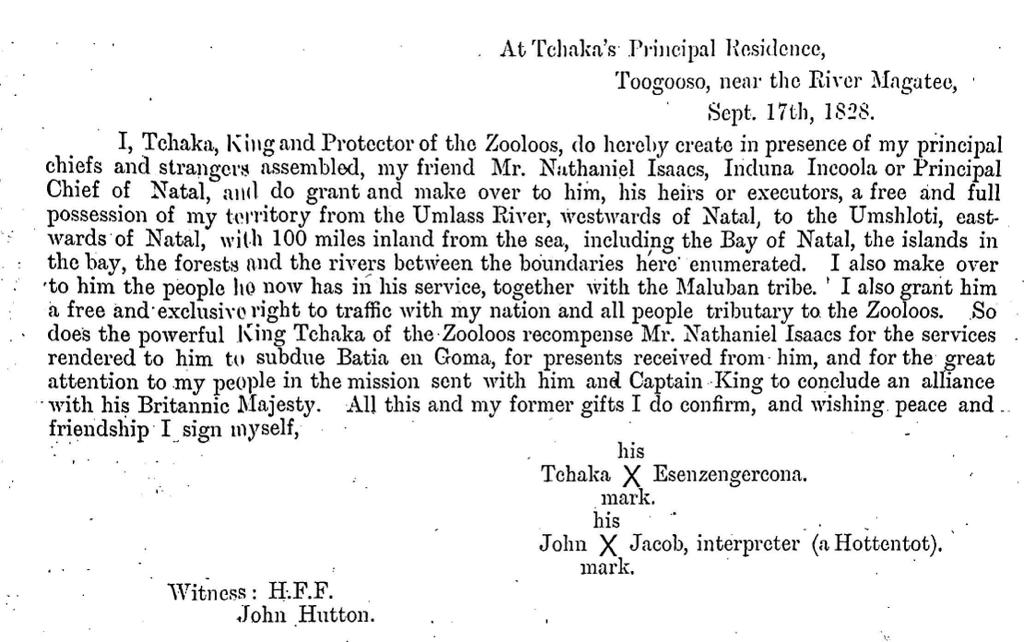

He shared the letter with the SA Jewish Report, which was recorded in the annual general meeting minutes of the South African Zionist Federation in 1905.

In the letter, dated 17 September 1828, Shaka wrote, “I, Tchaka [Shaka], king and protector of the Zooloos [Zulus], do hereby create in presence of my principal chiefs and strangers assembled, my friend, Mr Nathaniel Isaacs, indunu incoola or principal chief of Natal, and do grant and make over to him, his heirs or executors, a free and full possession of my territory from the Umlass River, westward of Natal, to the Umshloti, eastwards of Natal, with 100 miles in land from the sea, including the Bay of Natal, the islands in the bay, the forests and the rivers between boundaries here enumerated.” He wished Isaacs “peace and friendship”. It’s unclear how the letter came to be translated.

The information happens to coincide with the newly-released Mzansi Magic TV series Shaka iLembe, which looks at the life of the Zulu king in a whole new light. Though Isaacs doesn’t feature in the series, his connection to Shaka was recorded in his diary, which in turn shaped much of the West’s perceptions of the infamous warrior.

According to The Jews in South Africa: An Illustrated History by professors Richard Mendelsohn and Milton Shain, Benjamin Solomon, a non-practising English Jew, was one of the first Jews to settle in the Cape, coming via St Helena. Isaacs was his cousin, who “became an intrepid adventurer, far beyond the Cape frontier and an associate of the Zulu kings, Shaka and Dingaan”.

They write that Isaacs was “a young Jewish adventurer and trader who lived among the Zulus in the late 1820s. He recorded his experiences in Travels and Adventures in Eastern Africa, first published in London in 1836. The book became a seminal text on the reign of Shaka, the founder of the Zulu kingdom. This flawed and self-serving account, driven by Isaacs’ desire to paint a negative portrait of his hosts to encourage colonial expansion, is nevertheless a valuable contemporary source.”

It is in this account that Isaacs described how the people came to him indicating that they were ill, and, “I directed them to make some chicken soup.” About King Shaka, he wrote, “We went towards the palace to pay our respects, when Chaka [as Isaacs spelled his name] with a jocose manner and an artificial smile, told me to point out the part where I was wounded. I complied, and when he observed, ‘That is a cowardly sign, you must have turned your back towards your enemy, and if you were my man instead of King George’s, I should have you killed, I was silent, and thanked heaven for making me a subject of the king of England instead of the king of the Zoolas [as Isaacs spelled it].’”

However, the two grew to have respect for each other. Isaacs accompanied the Zulus in an expedition against a Swazi tribe, in which he was wounded. He was given the name Tamboosa, meaning “brave warrior”. In 1828, Isaacs had rank and honours conferred upon him, and he learned to speak Zulu fluently.

Isaacs wasn’t the only Jew to interact with the Zulu kingdom. Mendelsohn and Shain write that in December 1835, Benjamin Norden paid a semi-official visit to the Zulu kingdom on behalf of Sir Benjamin D’Urban, the governor of the colony at the Cape of Good Hope.

So how did Isaacs manage to get to the Natal region? According to the late writer Dr Louis Herrmann, “Nathaniel Isaacs was born in Canterbury in 1808 of a Jewish family of Kent. His father died when the boy was very young. His mother sent him to St Helena to stay with her brother, Saul Solomon, at the tender age of 14. Mr Solomon was a merchant at Jamestown on St Helena. In 1825, the brig Mary, commanded by Lieutenant King of the Royal Navy, arrived in St Helena with goods consigned to Solomon. Here, he met the 17-year-old ‘lively youth’ Nathaniel Isaacs, who convinced his uncle to join King on his onward voyage to the Cape. They arrived in Cape Town in the beginning of August 1825.”

In Cape Town, King heard that an old friend of his, Mr Farewell, an East India merchant, had been absent for more than 16 months and was stranded in Port Natal. King decided to undertake a voyage to Port Natal and left with Isaacs as a companion to find his “long absent friend”.

The brig Mary arrived at the bluff point, named Cape Natal, the entrance to today’s Durban Harbour, but she ran aground due to severe gale force winds. Everyone got on shore safely, but most of the equipment and baggage on the ship were washed overboard. They established that Mr Farewell and his party were alive and well, thus achieving the purpose of their journey, but ended up without a ship to take them back where they came from.

Isaacs then decided to explore the interior. His party reached Shaka’s kraal, 130 miles (209km) inland, and was received by the monarch, who already knew King. Isaacs observed tribal life at close quarters, and wrote about it in his journal.

At one point, Isaacs found his way back to the Cape, where he called for the British annexation of Natal. On his return to Natal, he became acquainted with Dingaan, who confirmed Shaka’s grant of land to him.

English traveller Henry Francis Fynn, Farewell, and Isaacs established the town of Port Natal, later renamed Durban. Today, there’s a Nathaniel Isaacs Park, a Nathaniel Isaacs Crescent, and a Nathaniel Isaacs Road in Durban.

Isaacs ultimately left Natal in 1831 when he heard that Dingaan was preparing to massacre the few whites living there. In 1844, Isaacs abandoned his claim on the land granted to him by Shaka, and settled in Sierra Leone, where he built up a thriving business.

In 1854, he was accused of slave-trading by the governor, Sir Arthur Kennedy. Isaacs got wind of his impending arrest and left for Liverpool, where spent the last years of his life. Kennedy was appointed governor of New South Wales in Australia, and took the papers relating to the slave-trading charges with him when returning to England before taking up his post in Australia. The papers were lost when the ship in which he was travelling was wrecked. In the absence of the papers, the English courts refused to proceed with prosecuting Isaacs.

Isaacs died on 26 June 1872 in Egremont, and is buried in the Canterbury Jewish Cemetery.

In recent years, many academics have questioned the accuracy of Isaac’s writings. Dan Wylie, an academic at Rhodes University who has written books on Shaka, asserts that Isaacs deliberately exaggerated the extent of Shaka’s brutality to boost the sales of his book. But other historians have challenged Wylie. Petros Sibani, a historian and tour guide of Zulu battlefields, said there was no doubting that Shaka “was a cruel and ruthless man, but they were cruel and ruthless times”.

Paula

June 29, 2023 at 10:09 pm

The Zulu kings, Shaka and Dingaan, were forces to be reckoned with. I studied History for Matric at Springs Girls High.

Our formidable teacher, a legend in her time, was Maureen O’ Gara.

Her wonderful sense of humour made our lessons that much more inspiring.

What an amazing account of the Jewish explorer and traveler, Nathan Isaacs. Who would have thought Isaacs was curing the Zulus with Jewish muti, “chicken soup!”

Sbu nkosi

July 4, 2023 at 5:55 am

Nonsense