Featured Item

The secular Jewish renaissance sweeping Israel

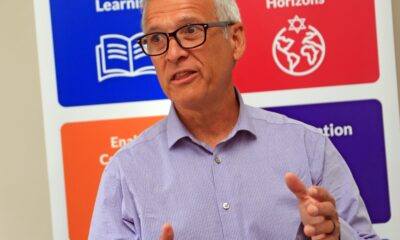

While 40% to 60% of Israeli Jews identify as secular, it’s not the kind of secular most people imagine it to be, said American-Canadian-Israeli queer Jewish educator-activist Elliot Vaisrub Glassenberg.

“It’s kind of its own unique thing,” Glassenberg told a Limmud Johannesburg audience last weekend. “They range anywhere from being agnostic to practising Judaism, vehemently atheist, to people who are deeply connected to Judaism and maybe even believe in G-d, but don’t sit in synagogues, except maybe at Yom Kippur just to hear the shofar,” he said.

Speaking from his own experience growing up in Chicago, Glassenberg described his experience with Judaism as being secular-refo-conserva-dox. This means his family would walk to shul every Shabbat, but would come home from shul and watch exclusively Jewish movies.

Similarly, he attended a Jewish school in Chicago, but for him, “Judaism is being Jewish. It’s going to synagogue; it’s praying; it’s hearing the Torah; it’s keeping kosher; it’s keeping Shabbat. And giving tzedakah. But it’s also Jewish humour, literature, and stories.”

“A lot of people, when they make aliya, stop going to synagogue or stop keeping Jewish traditions because for many, like me, one of the main reasons I went to synagogue was to connect to the Jewish community,” said Glassenberg. “In Israel, I have a Jewish community in my day job and in my day-to-day life. So, I had to question what Judaism looks like to me without those Jewish institutions.”

Glassenberg described the majority of Israeli secular Jews as like the son from the Pesach seder who doesn’t know how to ask.

“Many Jews were growing up not even knowing what questions to ask about their Jewish identity. But then they started asking questions: why are we here? What are we fighting for? What does it mean to be Jewish? What does it mean to be Israeli? What does it mean to be an Israeli Jew?

“People started asking questions. And secular Israelis started creating Jewish groups of secular Israeli prayer. Artists started integrating Jewish texts more into their art, and exploring what it means to be a Jewish Israeli artist,” said Glassenberg.

“This idea of the Hebrew cultural renaissance, that we need to create new forms of connection to Judaism, was something that was thriving in the early 1900s outside of Israel and in Israel.”

The turning point in this process was the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 by right-wing religious extremist Yigal Amir.

“Many secular Israelis who up until that point, and especially youth movements, were kind of ignorant or ambivalent about Judaism became antagonistic towards Judaism. They would say, ‘It was Judaism that killed Rabin. Judaism is anti-peace. Judaism is anti-LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender], and anti-women, and all this’,” said Glassenberg, “but then underneath that, there was a countercultural movement of small groups of Israelis saying, ‘That’s not Judaism. I know there’s more to Judaism than that. My parents didn’t teach me, but I know there’s more.’ These people went to find out how to recreate a Judaism that’s true to the values of their grandparents, the people that established the state of Israel and the kibbutzim.’”

Similarly, Glassenberg has witnessed a shift in the secular Jewish community since the right-wing government came to power in Israel and since 7 October. “A lot of secular Israelis, or I might even say liberal Israelis, had a big wake-up call when this new extremist right-wing government was elected and tried to do things that shook the status quo in Israel,” he said.

“There was what we call a social contract in Israel. Many secular Israelis would like things to be more secular, more democratic, and more liberal. Many religious and right-wing Israelis wanted things to be more conservative and more religious. There was a status quo of tension, a delicate balance – or imbalance – and this new government said, ‘You know what, we’re just going to change the rules of the game. We’re going to change the power of the Supreme Court. We’re going to pass dozens of new laws. But include religious coercion, perhaps reintroducing discrimination against LGBT people. And also, we’re going to start introducing mandatory Jewish Studies in secular schools, but it’s going to be overseen by Orthodox people.’

“So, there’s pushback on all of these things from all kinds of Jews. You see people fighting for the need to have a democratic state, not just a Jewish state. But something that’s different from the 1990s is that they’re saying we need a democratic state because that’s what our Judaism is,” said Glassenberg.

Furthermore, since the events of 7 October, “deep pain and trauma is prevailing all of Israel. A lot of secular Israelis needed sources of strength and spiritual support. When they felt like the ground had been taken out from under them, their sources of support – the army, the land, and the state – were also taken out from under them. Many secular Israelis were seeking Jewish sources of support,” he said.

Glassenberg said many of these secular Jews had been looking toward prayer and rituals like Kabbalat Shabbat to gain strength over the past 10 months, even having Kabbalat Shabbat at Hostage Square in Tel Aviv.

“It’s not like secular Israelis are suddenly showing up in Orthodox synagogues. But they want to use the Jewish tools that exist on their terms and in their way to provide strength and support.”