News

The story of our own book collector’s paradise

JORDAN MOSHE

The Treasury’s story began when Zelda Klass arrived on the shores of South Africa from a little shtetl in Lithuania. She had almost nothing but the clothes on her back and her name.

She went to live in Kimberley and eventually made her way to Yeoville in Johannesburg, where she and her husband started making a living selling ginger beer. They then moved on to selling babies’ items and several other things besides.

Zelda may not have started the book store (it was opened by her grandson, Geoff Klass), but her enterprising spirit lives on in Africa’s largest book store.

“My father was a book collector,” says Klass. “He collected books in the sense that he bought what he liked, not what was necessarily collectable. The home in which I grew up was full of books, so they have been a part of my life since the beginning.”

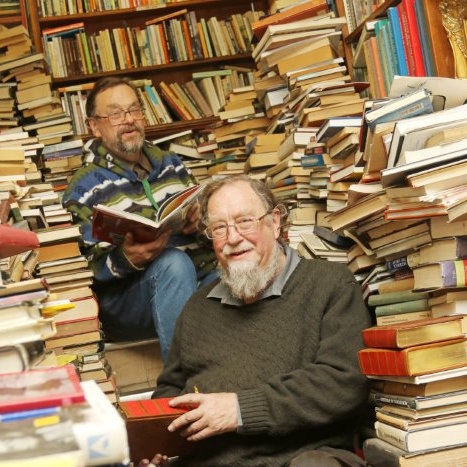

Immediately on entering the bookstore, visitors can affirm that this legacy remains alive. With more than two million books cramming the shelves, you’re greeted by piles of volumes, starting right by the front door. Books are packed against every wall, wedged into every corner and stacked atop any surface that will support them. Ceiling-high piles tower above your head, brush against your elbow and threaten to trip you if you don’t watch where you step.

In addition to books, you will find maps, prints, engravings, newspapers, photographs and thousands of vinyl records, as well as a small selection of decorative art antiquities.

The Klass brothers, Geoff and Jonathan, have been in business since 1974. Over the past 44 years, their trove of literature has been housed at various addresses in Johannesburg. Beginning at what is today the trendy 44 Stanley – where they paid a rental of R385 a month – they progressed eastwards, moving to Pritchard House for five years, then on to a neo-classical building at 63 Rissik Street in 1984, and finally settled at their present address in 1991, which they found and bought within three days.

Geoff Klass obtained a postgraduate degree in History and Philosophy of Science, and was then offered a fellowship in Chicago. “I chose to turn it down and instead opted to establish the shop with my late mother and brother,” he says. “We had worked in hotels for a while – my grandfather owned the Johannesburg Ritz Hotel as well as the Radium Beer Hall, and my father owned the Residential Hotel in Berea.”

Klass reflects on his decision to pursue book trading, and says that while regrets are part of life, his choice is not one of them. “I’m a medical historian by training. According to the Van Wyk de Vries Commission report on South African Universities of 1975, medical historians were one of the top three most retrenchable members of university staff at the time.

“So, it seems I made the right decision,” he laughs. “I’ve never worked for anyone but myself, and I’m exposed to things that others never get the chance to experience. People, ideas and objects from across the spectrum come into my life daily, and I think it’s phenomenal. My life is a constant context of discovery.”

And it includes many an odd encounter. “The number of times visitors have asked me ridiculous questions are too many to count,” says Klass. “From ‘Have you read every book in here?’ to ‘Can you tell me what book is at the bottom of that pile without looking?’, questions become more ridiculous every day.”

Klass explains that his work has both its joys and its concerns, including bureaucracy. “There is an increasing feeling that the government has a hand in your pocket more and more often,” he says. “The costs of running any business today are onerous. The rates we pay go up, but the prices can’t go up at the same pace. We have no fixed source of supply and so find ourselves working harder to run faster, just to be able to stand still and not fall back. Some days I lie awake and feel very tired of it all. I often feel I work much too hard.”

However, his joys far outweigh these concerns. “The opportunity that my work affords me to find new things I didn’t even know we had here are incredible,” he says.

“Sometimes a customer will find something hidden in a pile in the store and we can return it to where it belongs. There are people whose private collections we have helped build. We even have the odd person saying that this shop is better than The Strand in New York, the world’s largest second-hand bookstore, which is always cheering.”

Despite the rise of the Kindle and other e-book readers, Klass is certain that the printed book will continue to enjoy popularity for years to come. “Last year, there were more books produced than any year since the printing press was invented,” he says.

“Also, two-thirds of youth in the UK were found to prefer printed books over e-readers. The book is here to stay, and the Kindle is the one disappearing. I’ve never really feared the digital revolution. I knew it would come, and felt that if it did ever take over, real books would remain popular amongst collectors who still wanted actual books, so the trade would still exist.”

However, he maintains that the electronic book does have its uses. “E-readers and Kindles are ideal for textbooks,” says Klass. “Instead of printing and reprinting subsequent editions of a textbook, it makes more sense to format the contents in digital format and issue updates electronically. Britannica Encyclopaedia recognised this, as their books are updated almost daily. They only print to special order.”

Klass says that unlike e-readers, he is perfectly compatible with any book he chooses to pick up – he doesn’t need any updating or upgrading. “You can’t say the same of the Kindle,” he says.

What Klass does lament, however, is the way in which the rise in technology is destroying the creative process. Retrieving a copy of the collected manuscripts and drafts of George Orwell’s 1984, he points out the presence of crossed-out words, comments, alterations and rewritten sections. “When a book is written today, the creative process behind it can’t be seen the way it could in the past,” he says.

“When you type up a book on a computer, you can delete something or edit it and what existed before will not be seen again unless you save it. We can’t see the mind at work any longer, nor the mechanisms and processes which inform the process of writing.”

Klass’s hope for the future is merely to maintain stability in business. “When it comes to this type of work, there’s only so much we can do,” he says. “We’ve done all we can, but success depends on the public’s taste in literature as it develops. Still, today’s generation is reading more than that of the ’90s, so I am quite hopeful.”

He concludes: “In a funny way, the hipster movement has helped. Its adherents glory in retro, so the old-fashioned sees the light again from time to time. This suggests to me that there is still interest in things that some consider to be outdated, and that an appreciation of books still exists.”