OpEds

The variant that scuppered our new-year hopes

Since its arrival, COVID-19 has challenged physicians to gather evidence and make firm decisions. This isn’t a behaviour to which good evidence-based doctors are accustomed.

A fair, scientific development of a pathway of care is usually the exploration of an idea, an attempt to falsify it, and only when it proves reasonable, recommending it.

When the National Institute for Communicable Diseases announced a new variant of the SARS-COV-2 virus on the shores of South Africa that had three mutations in its spike proteins that could possible lead to a different disease picture for our population, I took the position of simply raising an eyebrow. This meant that I noted the transparent efforts of the South African government in contributing to international knowledge, and I labelled this finding in my mind as probably not significant. Many of my colleagues adopted the same approach.

Viruses mutate. The SARS-COV-2 virus had shown little mutation since its appearance, and a mutation such as this seemed inevitable.

Furthermore, mutations in viruses often result in the weakening of their clinical picture. We all remember how every case of swine flu required admission in 2010. Now, swine flu is largely defeated at home. Indeed, this new variant may have been good news. This was perhaps finally a COVID-19 natural evolution in a positive direction.

The predictions I made were wrong. A month later, this new variant has shaken our world. I field calls daily of young, healthy individuals who seek my advice regarding the “summer flu” they have contracted.

Most of these callers are either intrigued or adamantly object when I suggest that their rather typical COVID-19 symptoms of headache, sore throat, and either diarrhoea or sinus pain could in fact be COVID-19. Interestingly, the denialism is often fuelled by the fair logic that since they have followed the rules of social distancing, mask wearing, and sanitising, how could it be possible that they contracted COVID-19?

After some convincing, I manage to send them off for a PCR test, and perhaps 20% to 30% of these patients’ swabs are coming back positive.

Professor Salim Abdool Karim, the chairperson of the government’s Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19, cited this week that a working group had demonstrated over a sample of 100 000 cases that the new variant (officially named 501Y.V2) is 50% more transmissible than last year’s variant.

It explains why so many more patients are accessing their doctors and testing positive now. Eighty percent of analysed new cases in hotspot areas are indeed the new variant. We can blame Rage and irresponsible behaviour for this devastating second wave in South Africa, but the reality is that this variant should share part of the responsibility.

This has been a difficulty week in our practice, and we aren’t alone. Every day or two, a patient of the practice or a patient related to a patient of the practice has succumbed to this dreadful virus.

We have admitted a patient to hospital for high-flow oxygen and intravenous steroids almost every day. Doctors are trained to be saviours, and it feels disempowering so often to have to shift into the role of empathy only because all other options are exhausted.

I’m encouraged, however, by more community members becoming more cautious with regards to the virus. Fear drives caution, and caution saves lives. So, fear has been positive.

I’m also encouraged by the countering statistics reported by Dr Mary-Ann Davies from the department of health, Western Cape, where the probability of death over a 30-day period was compared between the two waves. The study concluded that there was “no difference in mortality by age group between the waves”. This reliable evidence seems contrary to what we have experienced on the ground, but it’s worth noting as a beacon of hope.

The tentacles of the spikes of this variant have reached further than expected – into our schools, shuls, and places of work. We all realise that hope for a new reality as we began 2021 was a pipe dream.

I don’t think anyone predicted the level of restriction COVID-19 has re-imposed upon us. I have been flooded with the question, “Should my kids be going to school orientations and younger kids back to pre-school?” We learnt last year that with the correct controls, schools aren’t cesspools of COVID-19 spread. In fact, they are probably the safest place for our kids to be. Nevertheless, I have adopted the position that over this brief spike, other than short safe orientation days where I believe guards are up and the probability of lax behaviour is low, we shouldn’t be sending our kids back to school yet.

I’m aware of the tremendous strain that home schooling is placing on families – emotionally, financially, and logistically. However, after a long meeting with a group of academic doctors who advise one of the community schools, I agreed that it made no sense to send young children to school. Unfortunately, they are poor adherers to social distancing and scrupulous behaviour, so it isn’t wise to go back to school in the face of a more contagious variant when hospitals are near capacity and ventilators are unavailable.

The value we give to life – even one life – overpowers the tremendous inconvenience we are experiencing. The status quo isn’t a long-term solution. As soon as health facilities are coping well again, I believe children should return to school with safety measures in place.

The second wave in South Africa has been devastating for so many in our community. Now is the opportunity for each of us to reach out in support of those personally infected and affected.

Let’s take this variant as a cue to a better type of approach and formidably march forward in our determination to overcome this pandemic and get ourselves back to normal life. I look forward to “variants” of novel treatments, newer and more efficient screenings, even vaccines.

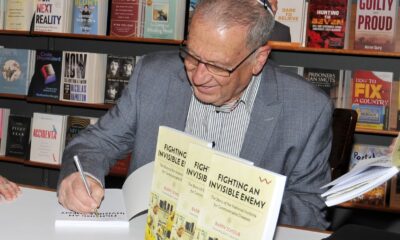

- Dr Daniel Israel is a family practitioner in Johannesburg.