News

The wanderlust of the Jewish Don Quixote

History shows that in addition to being called “the people of the book”, we Jews have undoubtedly earned the title of seasoned traveller.

JORDAN MOSHE

When we’re not learning, we’re wandering, and even when we learn, we often learn about wandering. Our journeys frequently take up our prayers and religious practices.

Though the catalysts for our various peregrinations have varied, it is Benjamin of Tunyedevka whose journey was inspired by the oddest catalyst of them all: a date from the holy land.

Benjamin is one of the many unique personalities created by Minsk-born Yiddish writer Mendel Mocher Sforim, the pen-name of Shalom Jacob Abramovich.

Born in 1836, Abramovich is recognised by all the great Yiddish writers as the zeida (grandpa) of Yiddish literature. He was the first enlightened Jewish author to write in Yiddish as opposed to Hebrew. He attempted to influence the Jewish people to free themselves from the physical and intellectual restraints of the ghettos of Europe.

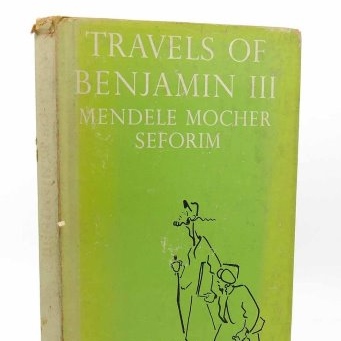

It is these Jews and their apparent complacency with living provincial lives who fuel his major work of 1878, Masos Benyomen Hashlishi, (The Wanderings of Benjamin III). Until today, it is considered by some to be the greatest satire on Jewish life in exile.

Benjamin – a bumpkin by all accounts – is shaken to his core by the arrival of a date from Israel while at home in his shtetl of Tunyedevka. The fruit inspires him to travel the world.

The wonder with which he describes the simple fruit is visually rich. “A Bible was brought to prove that the very same little fruit grew in the holy land. The harder the Tunyedevkans stared at it, the more clearly they saw before their eyes the River Jordan, the Cave of the Patriarchs, the tomb of Mother Rachel, the Wailing Wall. They bathed in the hot springs of Tiberias, climbed the Mount of Olives, ate dates and carobs, and stuffed their pockets with holy soil to bring back to Tunyedevka. For a moment, the whole of Tuneyadevka was in the land of Israel.”

Benjamin dives into travelogues and travel literature, thirsty for whatever descriptions he can find of the world beyond the shtetl. He prepares himself for the journey by venturing alone into the local forest, and getting lost in the process. Hearing a voice in the distance, he immediately imagines it to be a highwayman. Despite initially being overcome with fear, he steels and reprimands himself, “For shame, Benjamin! You dream of voyaging to far deserts and oceans teeming with griffins, hydrae, and anthropophagi, yet tremble at the thought of encountering a robber in the forest? I swear, I thought better of you!”

These words achieve little. Although he discovers that the suspected highwayman is simply a peasant driving a cart, Benjamin faints, wakes up in the cart, and believes himself taken captive by Arabs. Like Don Quixote before him, he believes every fanciful thought which enters his head, and embarks on a journey with his own Sancho Panza, a fellow-Jew called Sendrel.

Unlike Quixote, whom few actually take seriously, nearly everyone believes Benjamin’s delusions of grandeur. In fact, the act of setting out on the road makes him a hero. He is even suspected at times of being the Moshiach.

This work of satire is said to be inspired by an actual Jewish traveller called Benjamin, who lived hundreds of years earlier. This Benjamin was born in around 1127 in the city of Tudela, located in the northern Spanish province of Navarre. Benjamin of Tudela is the author of one of the most famous early travel books, Massaot Shel Rabbi Benjamin (The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela).

A rabbi by training, he set out on a world journey around 1159. During the next 14 years, he travelled to areas in Greece, Syria, ancient Palestine, Mesopotamia, Persia, and Arabia. He is also believed to be the first European to approach the Chinese border. He visited 300 cities in all, including many of importance in Jewish history.

The book he wrote to describe these travels, first translated in the 1840s, gave scholars one of the first eyewitness accounts of life in the Middle Ages throughout parts of southern Europe and the Middle East. Benjamin included fascinating descriptions of the physical conditions under which Jewish people lived in these regions, as well as politics, trade, and geography.

So, when you’re next looking for inspiration to set out and see the world, perhaps Freshfellas or some other well-stocked greengrocer might be the place to start.