Featured Item

Trauma, victims, and perpetrators – the psychology of abuse

For victims of abuse, the resulting trauma can have long-lasting repercussions. We may seek to understand and rehabilitate perpetrators, but our primary responsibility is to help the victims heal and to prevent future abuse, says Rabbi Avrohom Union, an international expert on child sexual and domestic abuse.

“We don’t understand the vulnerability of trauma,” said Union, addressing rabbis and rebbetzins at Koleinu SA’s Conference on Domestic Violence and Child Sexual Abuse this week. Union is the rabbinic administrator of the Rabbinical Council of California, who also holds a master’s degree in psychology.

“Trauma results in a fundamental reorganisation in the way the mind manages perceptions. It changes not only how we think and what we think about, but also our very capacity to think,” he said, quoting Dr Bessel van der Kolk, a psychiatrist specialising in post-traumatic stress disorder.

Common effects of trauma include depression; anxiety; panic attacks; a sense of shame and worthlessness; and feeling emotionally overwhelmed, Union said. Victims may also exhibit self-destructive behaviours; flashbacks; as well as a loss of a sense of who they are.

Victims of trauma may also experience lasting physical symptoms including chronic pain and headaches. Statistics even reveal a higher rate of cancer among abuse survivors and other diseases that don’t appear to have an emotional component. “Understand that it’s a two-way street – changes going on in our mind affect our bodies and vice versa,” said Union.

When someone is abused, the limbic system in the brain, where we process nonverbal, emotional, and relational experience as well as our feelings and traumatic memories, is activated by the fear we feel. In such situations, we respond in one of three ways – fight, flight, or freeze.

“When the victim is being victimised, the sense of fear and danger shuts down the thinking part of our brains – the frontal lobe,” said Union. “They’re not going to fight if they feel they can’t fight. And they’re going to run only if they believe they’re able to run and if they are in fact able to. What commonly happens is that they freeze.”

The impact of this extends far beyond the event itself. “All that remains within our bodies,” he said. “You may think that it’s over. Therapists will explain to you that it’s not over because the body keeps that feeling. Once those systems have been activated, it’s very difficult to get them out.”

Yet not every trauma victim is going to experience such extreme, long-lasting effects. “A lot has to do with who we are as individuals, our family history, our personal history, and our genetic makeup.” But it’s important to understand the potential for such an enduring impact, something that can last for years regardless of how severe the abuse is perceived to be.

Union points out that perpetrators can be well-educated, highly respected individuals, or trusted figures including rabbis or therapists. “When it happens with a rabbi or trusted figure, it’s typically more damaging because you’re not only perpetrating the abuse, you’ve broken their connection with their faith.”

They can be friends of the family or family members themselves. “Statistics show that most abuse of minors takes place by people they know,” Union said. Perpetrators can be victims themselves. “That’s one of the tragedies of abuse – a large majority of these people aren’t monsters. There are some, but most have their own problems and issues. It doesn’t justify anything, but it helps us to understand abuse better and try to break the cycle.”

Paedophiles are generally the “monsters” we refer to, Union said. They fall into two categories: preferential – those who seek children as their sole source of sexual gratification, and situational – when the offender isn’t specifically interested in children but will abuse whoever is available.

Most sexual offenders think about their crimes ahead of time. It’s rarely an impulsive act. “Offenders most often know their victims, and use these relationships to set up situations in which a chosen victim can be sexually assaulted.” What’s more, they generally manipulate these relationships over time to commit sexual offences in a process known as grooming, which often leaves the victim mistakenly feeling responsible for what has happened. Perpetrators also often threaten, pressurise, or use guilt to keep their victims from telling anyone.

Perpetrators tend to justify their behaviour to themselves either through denial – refusing to admit they’ve done anything wrong; rationalisation by blaming the victim or circumstances; and minimising the event, denying the seriousness of the act or harm to the victim.

“Abuse isn’t a mental illness,” Union stressed, “nor is it caused by a mental illness. Many individuals who live with mental health issues don’t abuse.” However, he said, we do commonly see mental illness in perpetrators, particularly personality disorders.

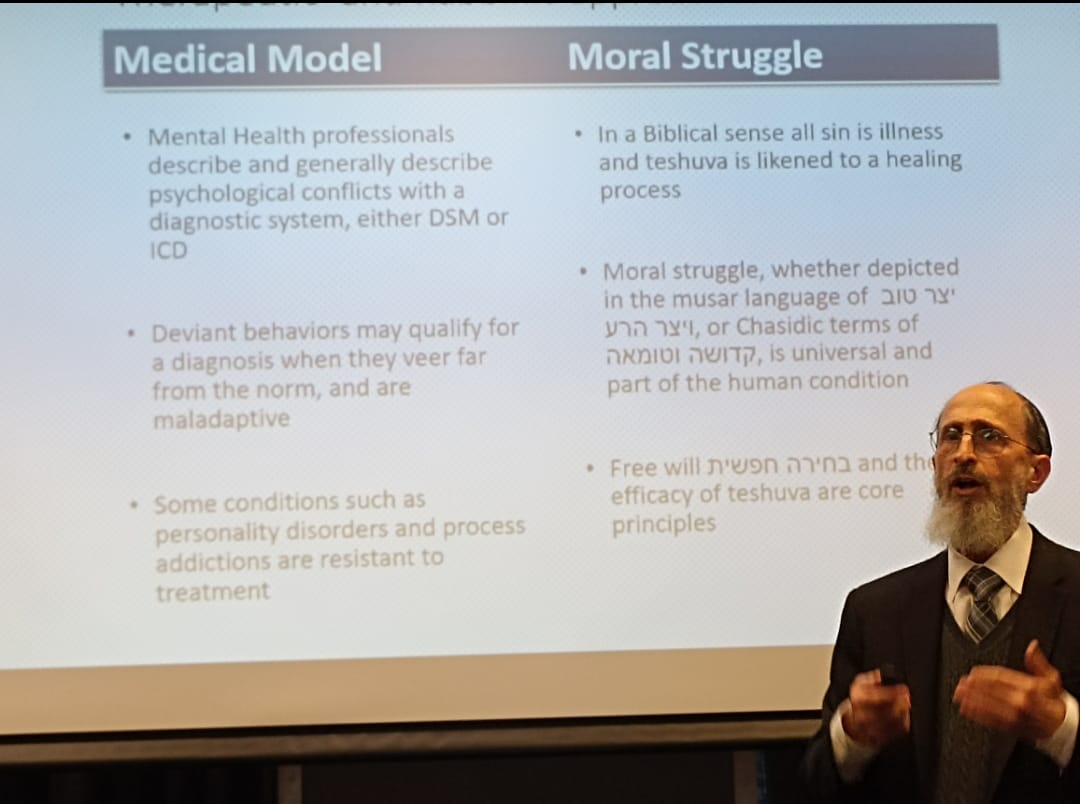

Union highlighted rabbinical approaches to the perpetrators of abuse. Rabbis generally think in terms of a moral struggle whereas mental health professionals speak in terms of diagnosis and treatment. In the moral-struggle model, sin is an illness, and the process of teshuva is likened to the healing process. This involves an admission of guilt, apologising to the victim, offering compensation, and taking active steps to change the behaviour.

Regardless of this process, our first responsibility is to the victim, Union said. Our mandate is to protect. We may feel sympathy for repentant perpetrators, but we cannot give them the opportunity to further victimise people by putting them in positions of power.

Many victims live with survivor’s guilt, however Union stressed that not everything that happens to us is deserved. “Halachically, a child cannot deserve abuse,” he said. By simply imparting this belief, rabbinic intervention in such cases can make a massive difference in healing. As such, he stressed the need for a partnership between the rabbinical and therapeutic world.

We can’t change the past but we can enable the person to move forward, Union said. “Healing doesn’t mean the damage never existed. It means the damage no longer controls our lives.”