News

Treasure trove of letters spotlights Jewish life in Nazi Germany

MOIRA SCHNEIDER

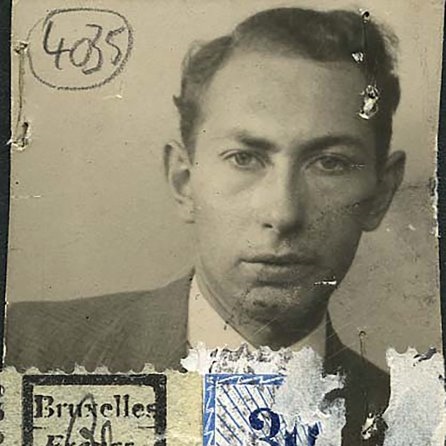

One of the few objects to have survived the fire was a large wooden trunk tucked away in the corner of the garage, containing thousands of letters. They belonged to Rudolf Schwab, Norman’s father, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1933 aged 21 and eventually found refuge in this country in 1936.

The extraordinary collection spans almost four decades – from the time of his arrival to his death in 1971 – and five continents across which his family had dispersed. The unique aspect of the correspondence is that it is more of a dialogue, since Rudolf kept not only the letters he received, but made carbon copies of those that he sent.

The letters are now the focus of an exhibition, “Letters of Loss and Refuge” at the South African Jewish Museum.

This exhibition is based on the book by Professor Shirli Gilbert, “From Things Lost: Forgotten Letters and the Legacy of the Holocaust”. Gilbert, who is professor of Modern History and director of the Parkes Institute for Jewish/non-Jewish Relations at the University of Southampton, wrote and curated the exhibition, having catalogued the letters.

Rudolf was born in 1911 to a prominent Jewish family in Hanau, a small city east of Frankfurt on the Main River. He fled the city in 1933, having been warned by his close childhood friend, Karl Kipfer, then a Nazi official, that he was to be arrested the next day.

In that year, there were 477 Jews living in Hanau who held prominent positions as doctors, lawyers, academics and businessmen. The persecution of its Jews began soon after the Nazis came to power.

Speaking at the exhibition’s opening, Gilbert said that the find was “by far” the largest collection of correspondence related to the Holocaust that she had encountered.

Poignantly, the collection includes letters until mid-1942 from family in Nazi Germany who were unable to get out.

Gilbert highlighted several threads in the exhibition: firstly, that the letters constituted a “vivid contemporary perspective” of Jewish life in Nazi Germany, rather than a retrospective one, as post-war testimonies are, describing the experiences of those who survived, when the outcome of events is already known.

“The letters, by contrast convey all the uncertainties and ambiguities of life as it was lived at the time, when the future was unclear.

“How did the family make sense of what was happening as new laws and restrictions were passed, as international opinion ebbed and flowed, as life around them disintegrated? What did they talk about and think about as the months and years rolled on?” she asked.

Secondly, it portrayed the tragedy of European Jewry in microcosm, with the scattering of Rudolf’s family to Shanghai, São Paulo, Buenos Aires, Stockholm and Montreal. While they may be regarded by history as the lucky ones to have escaped with their lives, in many cases their suffering was just beginning.

“The letters are proof that victimhood is a broad category, and that though it might be tempting, survival should never be romanticised,” Gilbert stated.

Thirdly, it put the spotlight on Rudolf’s friendship with Karl Kipfer, the Nazi official who had encouraged him to leave. “This was a very unexpected aspect of the correspondence,” Gilbert noted.

Though the two had lost touch after Rudolf left, they reconnected in 1948 and rekindled their friendship until Kipfer died in 1955. “This is probably the warmest and most prolific set of exchanges in all of Rudolf’s correspondence,” she commented.

Despite talking frequently about his “undemocratic past”, Karl never divulged to Rudolf what he actually did, but he devoted the remainder of his life to pursuing reparations from the German government for Rudolf and all his surviving relatives.

“His work on Rudolf’s claims was perhaps a way to process his sense of complicity, and restore his moral agency,” Gilbert suggested.

“As Karl put it, to ‘relieve the sorrows of my existence’

“He doesn’t fit neatly into the mould of perpetrator, but gets us closer to some of those questions at the heart of the Holocaust about the very complex motivations and inclinations that make us human,” Gilbert stated.

The letters were discovered eight years ago by Rudolf’s grandson Daniel Schwab who has devoted himself to having his grandfather’s collection archived, catalogued and studied. At the exhibition opening were Rudolf’s son Norman and granddaughter Ricci Lyons who is named after him.

“Until relatively recently I knew of my grandfather Ralph (Rudolf) as my father’s very stern father whose divorce from my grandmother necessitated my father spending all his school years in a Catholic boarding school,” Lyons told the gathering. There was also an absence in their lives of family from her father’s side.

“Jewish holidays were always spent with my mother’s family. Before the celebratory dinners we would go to Reform shul always thinking we were following our German grandfather’s family’s traditions.”

Thanks to her brother Daniel, Gilbert, the German translators and the Kaplan Foundation, Lyons said that she and her father now had “a very different and much deeper understanding of who we are and where we come from.

“I feel so blessed to be able to witness my father going through an incredibly cathartic process in his 70s by the realisation, through the medium of the letters, that whatever his father did, was well thought out and with the clear purpose of being in his young sons’ best interests.

“Now, from the letters, and the carefully written book, we know that the Schwab family was actually a very Observant Jewish family in Hanau Germany and that the main reason for Grandpa Ralph being Reform in South Africa was that was the community where he found acceptance and comfort and where he was able to continue his family’s commitment to their heritage and community by being an active member.”

The exhibition, which was designed by Angela Tuck, runs until October 8. The book’s website is http://www.wsupress.wayne.edu/fromthingslost/index.html