Featured Item

When can we expect a COVID-19 vaccine

With over 25 million cases, some 861 000 deaths and a monthly loss of some $375 billion across the global economy, COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc around the world.

The increasingly urgent question is: when can we expect a vaccine?

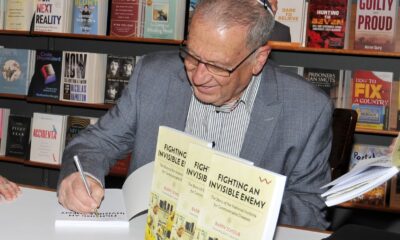

“We are in phase three of the vaccine trials, which means that we’re testing vaccines on groups of about 30 000 people,” explained pulmonologist Dr Anton Meyberg in a webinar on Sunday. “There are 203 trial vaccines with 26 clinical trials, and six of these [are] in phase three.

“We’re working incredibly fast. COVID-19’s virus genome was sequenced within eight weeks. We must remember that the polio vaccine took 60 years to be produced, and the eradication of polio has taken us 100 years in Africa.”

Meyberg explained that there are currently two vaccine trials being run in South Africa, each using a different approach.

He said: “The Chaddox trial by AstraZeneca uses a weakened form of the virus which is unable to replicate. The other is called NovoVax, and is being tested under the University of the Witwatersrand’s Professor Shabir Madhi. Both trials are testing the vaccines on patients who are immuno-compromised or are on HIV treatment.

“There are very interesting times ahead of us and we may have a vaccine within six to 12 months. It’s a big competition amongst companies, and a real case of winner-takes-all.”

COVID-19 aside, vaccine development involves a number of complex dimensions that need to be borne in mind. This is according to Professor Helen Rees, a foremost public health scientist and expert in the policy and science of HIV and vaccines, who presented last week during a webinar held by the SA Jewish Report.

“Two things need to happen very quickly,” she explained. “We need new therapeutic interventions to help the human host, and we also need to hamper the virus at the same time.”

She continued: “The first involves bolstering the host’s immunity in different ways, including altering conditions for viral entry, preventing excessive immune response, and opposing blood clotting. The second entails hampering the virus by interfering with it in a number of ways.”

Vaccines fall into the second category. According to Rees, when a vaccine is administered, the body’s adaptive immunity cells are activated, resulting in two responses.

“Antibody in B-type cells block infection and those in T-type cells act in certain ways to kill infected cells,” she said. “Once you have such a response, if your body detects another infection, it can kick it out again. This is what we’re trying to do with the COVID-19 vaccine.”

Rees outlined the typical vaccine development process, explaining that it typically involves not just a medical evaluation, but also an assessment of the commercial market and vaccine demand. The process involves assessing need and evaluating the commercial market.

“Is it a global demand or a niched one?” said Rees. “This is one of the considerations taken before the process even begins. After that, the first leg in a lab can take up to two years, followed by long phases of trials and testing on small groups, and then larger ones to test safety only.”

It’s only after safety testing that efficacy is tested, with thousands of test subjects involved in a mass clinical trial.

Said Rees: “This whole thing takes six to 12 years and, obviously, that’s really not helpful in a pandemic.”

For this reason, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI) was established in the wake of the 2014 Ebola outbreak. A major international organisation, the coalition is aimed at accelerating the development of emerging diseases, and simultaneously enabling equitable access for all counties to a vaccine. Consequently, preparedness for outbreaks is stepped up and any vaccine response is made globally sustainable.

“By doing this, the idea was to reduce the standard of 12 years to 18 months,” said Rees. “By consolidating trial phases, a vaccine could theoretically be rolled out within 18 months, with CEPI looking out for outbreak potential and developing potential vaccines against them.”

Among the potential viruses targeted is one known as Disease X, a term referring to a virus about which little is known, and in response to which a platform for a vaccine could be created despite a lack of information.

“CEPI is like a vacuum cleaner with a variety of different head attachments,” said Rees. “It aims to use existing vaccine platforms in turn against the novel virus. If one doesn’t work, you fit another head on. If you successfully identify a genetic sequence, you then plug in the disease pathogen and develop a vaccine using the successful platform.”

COVID-19 fell into the Disease X category when it was first reported in Wuhan, China in January this year, resulting in CEPI diverting funds towards preparing a vaccine. Its various vaccine platforms have become part of the worldwide vaccine development, said Rees.

“We have over 200 vaccines in development and 31 trials,” she said. “The issue right now is vaccine nationalism, meaning that we’re anticipating unprecedented demand for any effective vaccine, which will outstrip supply entirely for at least 12 to 18 months.”

This means that richer countries will make bilateral deals with developers, resulting in nothing being left for poor and low-income countries, and South Africa falls into this category. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) and other stakeholders have conceived a funding initiative aimed at ensuring that no country is left without access to a vaccine.

However, it can only ensure that a certain percentage of a country’s population will receive a vaccine, meaning countries will have to decide which groups are most in need of initial vaccine doses.

“We think that by 2021 we might have enough vaccines worldwide to give to some 3% of every country’s population,” Rees prognosticated. “Who do you give it to? The most vulnerable or healthcare workers? Perhaps those stabilising the economy?”

Much discussion and modelling are currently underway to plan distribution strategies, but it will ultimately be up to each country to prioritise for its own population.

“We are only safe if we are all safe,” said Rees. “We can’t have countries thinking they can immunise entire populations. Many populations won’t be protected, and if a continent is left behind, the virus will continue to circulate.”

“We’re not talking about the world having enough vaccines by 2021, but we must start somewhere. Distribution is a global discussion, and it’s likely we will have a graduated approach which is country-specific. We’ll only start to see enough vaccines worldwide by 2022 at least.”