News

Women come out of the cold in Israeli art

MIRAH LANGER

Timna Seligman, a curator at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, was in South Africa recently to share the story.

“In the general history of Israeli art, there is a standard canon in the way the artists are mentioned and the art is presented. Most of the artists are men. There are women as well, but somehow, over the years, they have become sidelined, especially from the earlier part of the 20th century,” says Seligman.

“Now, there is a journey of discovery as we try to find the women who were working alongside the men, but were not included in the narrative that was being told all the time.

“They were sidelined, but we are going back and looking for them, not only in the modern period, but going all the way back into the Renaissance.”

Seligman was giving a presentation about female artists throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century at the Rabbi Cyril Harris Community Centre in Oaklands, Johannesburg.

She said that the start of Israeli art is generally marked by the opening of the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in 1906. It was established by Bulgarian immigrant Boris Schatz, who conceived of the institution as “part of the Zionist vision of a new modern art for a new modern Israel – an art form that combines the best of the West and the East”.

In the 1920s, the influx of immigrants from Europe to Israel resulted in the emergence of more female artists. Like men, they often depicted local communities from a very Orientalist point of view: focusing on the idea of their exoticism and traditional dress, for example.

Many of the aspirations and perspectives of Jewish immigrants to Israel were captured by Anna Ticho, an artist who emigrated as a young woman from Moravia to Israel in 1912. In her drawing, “Old City of Jerusalem” from 1927, she depicts the city as “crowded and impenetrable”, says Seligman, who is based at Anna Ticho House at the Israel Museum.

“This is very typical of a lot of the artists who were coming to Israel at the time. As much as they would wander the streets of the old city, when it came to depicting it, they would always do so from the outside, looking in; they will always be the foreigner, they will always be the outsider.”

Ticho’s exploration of nature symbolises her Zionist beliefs, suggested Seligman, who herself made aliyah from London to Israel in the 1980s.

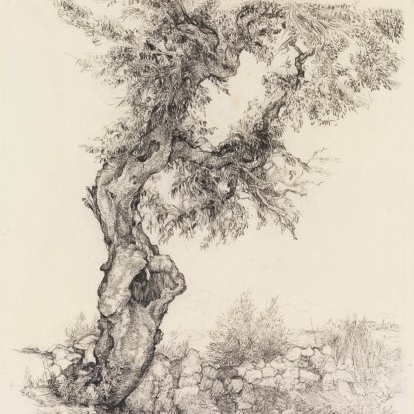

In “Olive Tree” (1935), Ticho depicts “the ancient tree that belongs to the land. It’s the tree that is rooted in the land, and it has gone through difficult periods all these years. It’s been damaged, hollowed out, branches are missing, but, still at the top, there are leaves, and there is fruit.

“You can see it very much as an allegory of the Zionist endeavour. This is our land. We come from here. We have had this difficult history in the middle, but we are coming back, and we are going to thrive.”

During the 1940s and 1950s, lyrical abstraction, stemming from European trends, became the focus of most male – and some female – artists. However, other female artists such as Ticho, as well as Ruth Shloss, explored a style and subject matter different to the norm.

These artists were interested in social awareness. They wanted to capture the realities of the new state of Israel – the huge influx of immigrants to the country and their experiences including poverty and overcrowding. “These kind of portraits aren’t really being done by men, this kind of sensitivity,” Seligman says.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Israeli art reflects worldwide trends, such as conceptual and performance art.

For female artists like Yocheved Weinfeld, feminist concerns were in the foreground. In her work, “Sewn Fingers”, from 1974, she shows a series of images showing a woman’s open hand slowly becoming stitched together until it is totally closed, “from being able to be active, to a hand that no longer functions”.

As the intifadas break out in the 1990s, female artists also began capturing their lived experience of this political environment.

In Hila Lulu Lin’s “Cold Blood: A poem in Three Parts” from 1996, “She has taken this typical view of Jerusalem, of the Dome of the Rock, the beach at Tel Aviv, and a self-portrait, and put across all of them the [image of a] slab of raw, bloody meat as the sky, as the eyes.

“It’s a disturbing image. It really does show that on the one hand, you are just living your life, there are even tourists going to the beach and having fun. But there is this impending doom, and it’s just hanging over Tel Aviv, hanging over Jerusalem, and within her as well.

“She’s not trying to give a solution or saying these people are right or these people are wrong. She’s just giving a picture of the situation at the time.”

In terms of contemporary art, Nirit Takele is one of many female artists giving a creative voice to traditionally minority communities. An Ethiopian Jew who came to Israel as a child during Operation Solomon, her style is a modernist Western one, and she twists many conventional expectations in her art.

For example, in “Studio Visit with Adam and Eve”, she depicts Adam and Eve as Ethiopian. She then places herself in the painting as a modern Ethiopian woman. “She is saying, ‘Yes, I’m Ethiopian, but I’m also Israeli. I know my history and my background, but I also know the wider background of the culture.’

“It’s new, it’s fresh,” asserts Seligman about the exciting developments that female artists like Takele keep adding to the story of Israeli art.