Featured Item

Women’s struggle to survive the Holocaust

All Jewish people fought to survive and care for their families as their world was ripped asunder when the Nazis rose to power, but Jewish women stood out for the particular burdens they had to bear.

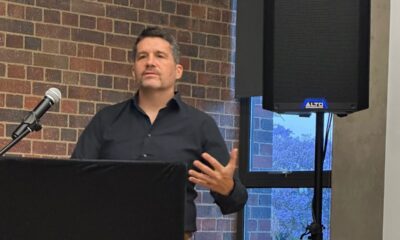

This was the premise of a talk given by Rabbi Moshe Cohn, the head of the Jewish World Section at the International School for Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem, on a webinar hosted by the Cape Town Holocaust Centre.

“The story of war is a story of rupture – ripping asunder everything we hold dear. From their role in society, to their jobs, to the minute-by-minute reality of their lives, Jews faced drastic change,” says Cohn. According to Warsaw ghetto diarist Emanuel Ringelblum, “It changed with the speed of a movie. Future historians will have to dedicate an appropriate page for women in the war for her courage and steadfastness. Thanks to her, thousands of families have managed to surmount the terror of the times,” he wrote in June 1942.

Cohn notes that there is a “great movement towards revisionist history. There are many who believe that we should change the way we understand history to fit today’s sensibilities.” He disagrees with this, emphasising that we need to understand history in its context. So, even though women are extremely liberated today, they weren’t then, and we need to accept this point if we are to understand the challenges they faced.

“Women’s roles were very well-defined. But from the 1930s onwards, many Jewish men lost their jobs, leading women to go out and find work. This led to role reversals, of women becoming breadwinners and men staying at home.” However, it wasn’t a simple switch, with many men being unable to accept the situation and often sinking into depression. They couldn’t partner equally with their wives, which meant women now had to play the role of breadwinner and mother.

“Women wanted to survive. Men tended to collapse. While this is a generalisation, there was a sense of men ‘folding onto themselves’, unable to accept their new position in the household. It was a foreign concept,” he says.

Then, after Kristallnacht on 10 November 1938, more than 30 000 Jewish men were arrested – almost 10% of the Jewish population in Germany. Many women were suddenly on their own, and had to try to rescue their husbands by protesting, writing letters, and so on, as well as working and taking care of the home and children.

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, many Jews fled towards the Soviet Union. Two thirds of these were men, leaving even more women alone to assume the role of both parents. “They also had to make impossible decisions on their own,” says Cohn. He showed a clip of one survivor saying how her mother’s role in life changed on 1 September 1939. She went from an elegant woman who had never worked, to one who did, battling every day to put food on the table and keep her children safe.

As Jews were forced into ghettos, they faced hunger, overcrowding, disease, and the ever-present threat of deportation. It was women who often had to navigate the horrendous choices and dangerous reality of ghetto life in order to keep their families alive.

Cohn explained that the black market was a key aspect, and women used it as a strategy of survival. However, this differed in each ghetto. In Warsaw, the ghetto was surrounded by Poles, many of whom also saw the Germans as the enemy. This allowed a black market to thrive. However, in Łódź, those outside the walls were occupying Germans. There were no ‘friends’ outside, and no black market. This drastically changed the strategy women had to use to stay alive and keep their family alive.”

Delving into some devastating statistics of life in the ghetto, Cohn says that 30% of Warsaw’s population lived in 2.5% of city, with six to seven people per room. In Łódź, conditions were even worse, with up to ten people per room, no gas to cook with, and tiny calorie intakes. In both ghettos, there was no privacy, even when going to the toilet. Hunger was all-consuming, and it was women who waged war with it.

Cohn showed extracts from survivor testimonies and diaries, describing how mothers went out to try and find food while their children huddled home alone, and the devastation when they found nothing. One woman brought back some parsley, and told her children to suck it in their mouths for a long time. Another survivor described a 14-year-old teenager crying from hunger like a baby to his mother. A survivor discussed how his mother ensured their food lasted until the next rations were handed out, and others described how women tried to provide special or extra food for Shabbat.

Many testimonies discuss the choice women faced whether to allow their families to eat unkosher meat if this was all they could get. The testimony of Sara Selver-Urbach in the Łódź ghetto describes her mother choosing to give her ill brother the unkosher meat, and attempting to keep a kosher and unkosher section of her tiny kitchen. Eventually, the entire family consumed the meat to try to survive.

Another survivor described his father saying that they must eat the unkosher meat to survive, fulfilling the commandment of pikuach nefesh (saving a life above all else). His mother disagreed, saying they would survive if they didn’t eat it. It was a “ferocious fight”. This attempt at continuity in the face of death is something many women took on. However, in this family, the husband forced his wife to prepare the meat, although she never ate it. The battle created a rift between the parents that they never recovered from.

Vladka Meed described how his mother chose to pay his brother’s Barmitzvah teacher with bread, even though it meant more hunger. This was her attempt at rising above her circumstances. “How much strength a woman needed! To be able to think in those days about my brother’s preparation for Barmitzvah!” he writes. “Women had a willingness to connect with the past in order to create a future, which helped many families survive,” says Cohn.

There are other instances like this, from making Shabbat special, to women leading a seder in the place of a man. Naomi Winkler Munkacsi described how a fellow Auschwitz prisoner told her, “‘I just lit the Sabbath candles – I saw two electric bulbs and said the blessing on them.’ Another time, on a Friday night in the factory, I saw a woman whose job was polishing small iron hoops and rings take some of the rings and arrange them into candles and candlesticks, as it were, and then cover her face with her hands and silently recite the blessing.”

Another survivor described an incident in which Nazis searched a house and removed the parchment from the mezuzah, threatening to burn it. “In her perfect German, my mother followed him, asking him not to burn the parchment, until he eventually threw it back at her. She risked her life for a piece of parchment. in my mind, it was Kiddush Hashem [sanctifying G-d’s name],” he said.

Cohn agrees. “It was an act of insane bravery and an exquisite statement of continuity and the battle against dehumanisation, saying, ‘I am a person and I demand you respect the symbols of who I am.’”

“From what magical stream does my mother draw strength for all of this? There must be some great hidden force, a force of love, a force of tremendous will to hold on and watch out for us,” wrote survivor Irene Liebman. Indeed, surmises Cohn, “Women worked to mend the rupture and maintain continuity, all to allow their families to be able to live as human beings and as Jews.”